Galaxies are the birthplaces of all stars, providing a nursery dense with massive clouds of gas and dust that collapse in on themselves over time. As this matter collapses more and more, it begins to heat up until fusion — the nuclear process that powers stars and forms many of the heavier elements in the Universe — takes over. In a burst of light and energy, a new star is born.

The birth of each new star is an incredible event that keeps galaxies bright. But why are some galaxies better at forming new stars than others, and are there circumstances that can rob a galaxy of this exceptional ability? To find out, researchers used a powerful radio telescope to look beyond visible light for clues.

Galaxies are being robbed of their gas

“We know that galaxies are being robbed of their gas,” explained Toby Brown, a Plaskett Fellow at the Herzberg Astronomy and Astrophysics Research Centre and lead author of the research published in The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, in a press release.

“If enough gas is destroyed or removed, star formation is shut down, effectively killing the galaxy and turning it into a dead object.”

To learn more about the processes causing gas to be removed from galaxies, Brown and colleagues used observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), a collection of 66 radio telescopes located in Chile’s Atacama desert. Because molecular clouds are cold and dark, they’re difficult to study and can’t be observed with visible light — but they do emit at longer millimetre wavelengths of light, which can be detected by ALMA.

The team turned their telescopes on the Virgo Cluster: an extreme environment made up of thousands of galaxies that whip by each other at millions of kilometres per hour. They were interested in learning how the extreme speeds and conditions in the Virgo Cluster affected the gas and dust within the individual galaxies.

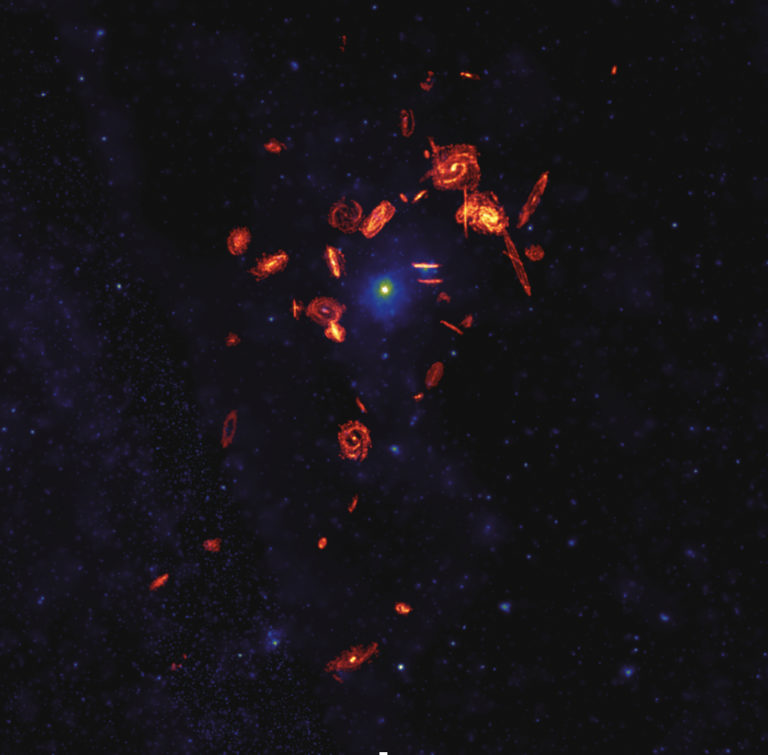

“[W]e looked at 51 galaxy gas reservoirs in the Virgo Cluster, which are the direct fuel supply for new stars, and provided many of the most detailed images of gas disks in cluster galaxies every observed,” Brown explained.

“These new images are incredibly useful for revealing how star formation in galaxies […] is shut down by external influence.”

The images from ALMA revealed just how impactful the extreme environment of the Virgo Cluster really was. By studying the images, Brown and colleagues were able to see the fingerprints of the Virgo Cluster’s extreme heat and speed within the galaxy’s gas disks, stripping them of the gas and dust they need to form new stars.

These observations represent the first large survey of molecular gas with high sensitivity and resolution in the Virgo Cluster. Going forward, the team plans to continue studying the Virgo Cluster’s environment to shed further light on the extraordinary processes that birth new stars.

To learn more, watch Toby Brown discuss this new research in a video from the National Research Council Canada: