How are your teeth like tree trunks? No, it’s not a trick question – it’s a new study from McMaster University.

Just like the rings of a tree can give you information about the tree’s environment at that particular time, the layers of your teeth can too.

A team led by Megan Brickley, Professor of Anthropology and Canada Research Chair in Bioarchaeology of Human Disease, developed this new method for tracking Vitamin D deficiency in early humans to help piece together clues about their lifestyle and migration.

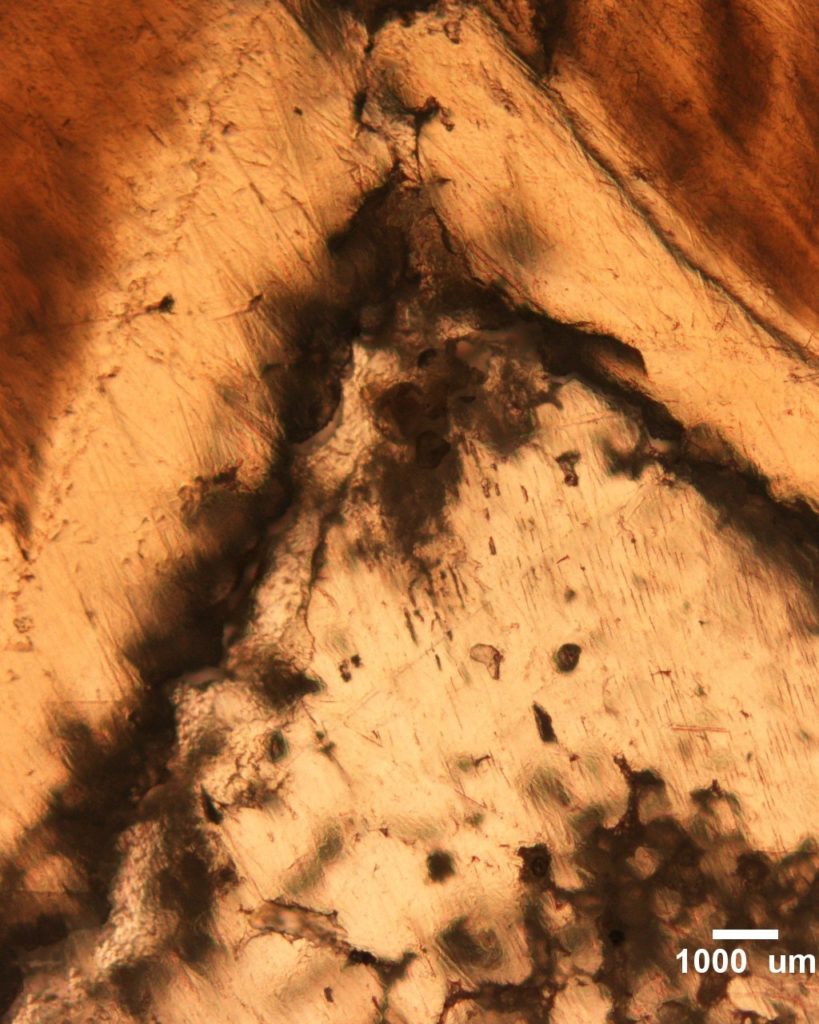

One of the things that tooth layers reveal is Vitamin D deficiency, which is related to sunlight exposure. New layers of dentin, the major component of your teeth, form throughout life. Without Vitamin D, the dentin cannot form properly and is riddled with pores, giving a bubbly appearance when observed under the microscope. By observing the location and thickness of these bubbly layers of dentin, researchers can get a good idea of when certain populations were lacking exposure to sunlight.

“More pronounced spaces indicate a greater level of disruption and the position of the bands of defects indicates that age at which deficiency occurred,” explains Brickley.

Exposure to sunlight is affected by a variety of factors including geographical location, style of clothing, style of shelter, and even diet, so finding evidence of Vitamin D deficiency in teeth is not an exact indicator, but it can be combined with other anthropological information to draw certain conclusions about lifestyle.

For example, the switch from simple farming to a more urban lifestyle would have a significant impact on Vitamin D levels as time spent outdoors decreases substantially.

Brickley’s team found that Vitamin D deficiency can be seen in teeth from as early as the Late Pleistocene, or tens of thousands of years old. Some of these may even be considered Neanderthal, which could help provide answers to some long-standing questions.

Evidence of Vitamin D deficiency in Neanderthals and other Homo species could shed light on changes in skin pigmentation after early humans moved out of Africa. Natural selection favours light coloured skin in areas where sunlight is rarer, since melanin, the pigment that turns your skin dark, acts as a natural sunscreen. By looking at the timeline of Vitamin D deficiency, a timeline for changes in skin pigmentation can potentially be inferred.

“We now have a proven resource that could finally bring definitive answers to fundamental questions about the early movements and conditions human populations,” says Brickley.