The Jurassic Park franchise may have led many movie-goers to believe that tyrannosaurids were fast, with one of the franchise’s most iconic scenes featuring a fully-grown Tyrannosaurus rex outrunning a Jeep. According to new research from the University of Alberta, however, these fearsome dinosaurs weren’t quite so quick — and they only became slower and less agile as they aged.

The study, which examined fossilized tyrannosaurid footprints, was published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

What’s in a footprint?

Footprints are an important tool for paleontologists. They preserve a record of an animal’s flesh and soft tissues that might otherwise be lost in a fossilized skeleton. This can provide paleontologists with greater insight into what an extinct animal might have looked like, or how its weight was distributed throughout its body.

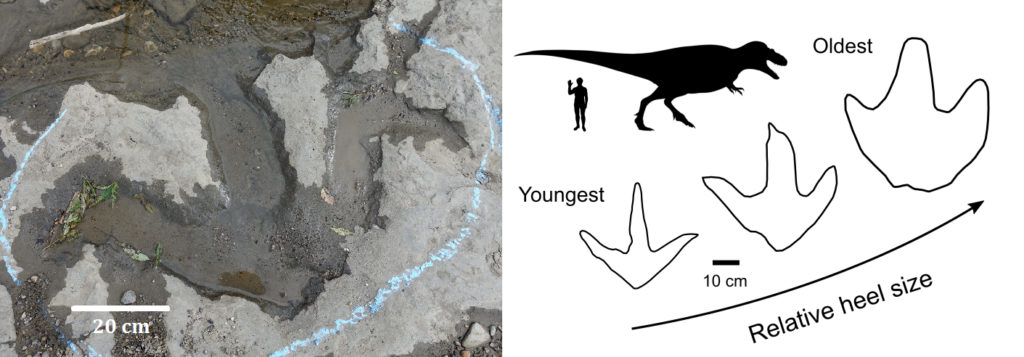

“[F]ossil footprints… are unique in that they can provide a snapshot of the feet as they appeared in life, with outlines of the soft, fleshy parts of the foot that are rarely preserved as fossils,” explained Nathan Enriquez, a PhD student at the University of New England and lead author of the study, in a press release.

For this particular study, Enriquez and his colleagues analyzed well-preserved tyrannosaurid footprints found mainly in the Grande Prairie area of Alberta. They couldn’t tell which species of tyrannosaurid produced the tracks from the footprints alone, but the fact that they were found in and around Alberta led the researchers to believe that they came from a species in the Albertosaurus genus, which is a member of the tyrannosaurid family, and a relative of the more well-known Tyrannosaurus rex.

The footprints ranged in size from 40-centimetre-long tracks produced by young tyrannosaurids, to tracks from older tyrannosaurids that measured more than 60 centimetres. By comparing the shapes of these different footprints, the researchers were able to draw conclusions about the dinosaurs that left them behind.

Tyrannosaurids became less agile as they aged

Enriquez and his colleagues noticed that the largest footprints, from the oldest tyrannosaurids, had proportionally larger heel areas than those from younger tyrannosaurids. Older tyrannosaurids likely had to adjust their walking patterns as they aged and gained weight, supporting more of their weight on the backs of their feet and becoming less quick and agile in the process.

“The smaller tracks are comparably slender, while the biggest [tyrannosaurids] tracks are relatively broader and had much larger heel areas,” explained Enriquez. “This makes sense for an animal that is becoming larger and needs to support its rapidly increasing body weight.”

This rapid increase in body weight would have made running difficult. Instead, older tyrannosaurids likely walked around at slower paces, supporting their large body weights across the entire area of their feet.

While a particularly good fossil record means that tyrannosaurids have been studied in great detail, less is known about how these animals grew and reproduced. Dinosaur growth in general is also an important area of study for paleontologists, with many questions still remaining about how these creatures grew to their large sizes.

Enriquez’s work will help fellow paleontologists understand how tyrannosaurids grew and changed throughout their lives, providing further insight into one of pop culture’s most beloved dinosaurs.