For years, astronomers have believed that galaxy formation in the early Universe was a chaotic process, resulting in galaxies totally unlike our own Milky Way. But new observations of a young galaxy in the distant past have challenged these beliefs, leading astronomers to question their current understanding of how galaxies in our Universe form and evolve.

The findings were published in Science, and included contributions from the University of British Columbia.

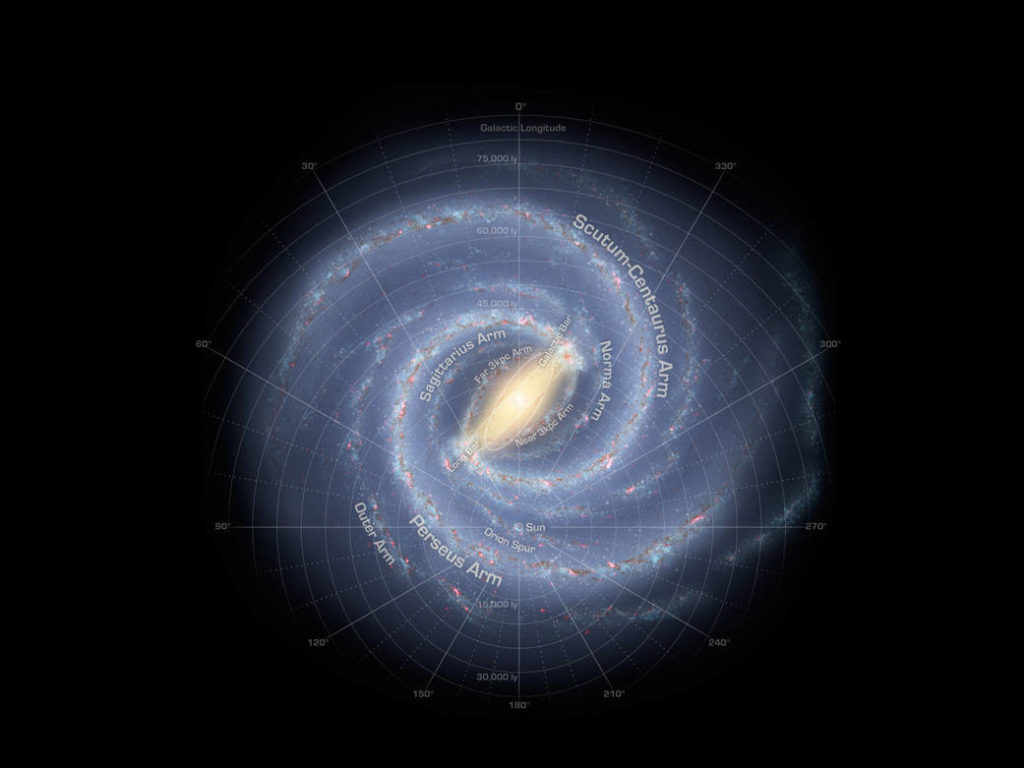

Until now, astronomers believed that galaxies like our Milky Way — large collections of stars with well-defined spiral arms and massive central bulges — form over billions of years, and are the result of many collisions between smaller collections of stars.

In particular, galactic bulges located at the centres of spiral galaxies like the Milky Way are believed to have been built up through many collisions that occur over many billions of years. This means that we shouldn’t be able to observe these particular features in very young galaxies that formed early on in the history of the Universe.

Using observations from the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array (ALMA) in Chile’s Atacama Desert, however, a team of astronomers did just that. The observations allowed them to peer more than 12 and a half billion years back in time to a period when the Universe was only 1.2 billion years old, revealing a young galaxy called ALESS 073.1 that appears much older, and much more well-defined, than astronomers believed to be possible.

“We discovered that a massive bulge, a regular rotating disk, and possibly spiral arms were already in place in this galaxy when the Universe was just 10% of its current age,” said Federico Lelli, a research staff member at the Arcetri Astrophysical Observatory and lead author on the paper, in a press release.

“In other words, this galaxy looks like a grown adult, but it should be just a little child. It defies our understanding of galaxy formation.”

At such an early point in the history of the Universe, there shouldn’t have been enough time for collisions to form a massive galactic bulge like the one Lelli and his colleagues observed. A much faster process must have been at work — one that doesn’t fit in with our current picture of galaxy formation.

“This work shows that bulges can form rapidly, counter to the expectation that they build up slowly over time,” added Allison Man, an assistant professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at UBC and co-author on the paper. “It will be important to understand if bulges are more common than thought in the young Universe.”

The team behind the discovery still isn’t sure exactly how this bulge could form so quickly and efficiently, but future observations of this and other galaxies with ALMA could help answer these questions.

By observing at millimetre and submillimetre wavelengths, ALMA is able to access some of the coldest, most distant light in the Universe, shedding further light on the mysteries of galaxy formation in the early Universe. Future observations will help reveal whether galaxies like ALESS 073.1 are more common than expected, or whether this unusually-mature galaxy is the odd one out in an early Universe full of chaos and disorder.