Preservation of primary human blood and tissue samples can be invaluable to research, and interest from industry and government agencies continues to grow. This practice is also known as biobanking, but there are legal and ethical issues that could leave biobank projects vulnerable. According to a new report by researchers at the University of Alberta, the broad consent forms that dominate biobanking are a legal time bomb.

Broad consent is typically obtained using a form issued at the time a sample is taken, permitting its use in general future research. These forms often still give options to decline the use of one’s sample in particular areas of research.

For researchers, it’s a relatively hassle-free option for gaining consent for general future use as new research projects arise – but it’s not watertight. Previous litigation has seen payouts and project terminations after participants took biobanks through the courts to remove their samples. The authors argue that broad consent is too loose and subject to the whims of public perception, which is vulnerable to misinformation and lies.

There is no agreement on a standard process for consent

Biobanks are like slow cookers in terms of their value – they facilitate huge projects that go on for years but produce incredible results. Thanks to biobanks, science gained insight into the prevalence and clinical outcomes of Hepatitis C, the characterization of different subsets of Dengue virus, and the efficacy of tamoxifen – a type of breast cancer treatment.

So given the long-term nature of these initiatives and their enormous positive potential, developing a ubiquitous and legally-sound consent policy is paramount. The problem is that there is no widespread agreement on how to approach this.

“Our own research has found no consensus among the public, legal academics, bioethicists, or privacy experts,” says Tim Caulfield, co-author and Canada Research Chair in Health Law and Policy. “Also, in some jurisdictions, there is often a disconnect between what is done and what the law and research ethics policy actually says.”

“Everyone wants this important research to proceed, but we need a sustainable policy. Indeed, given the growing interest in human tissue, these issues seem likely to intensify.”

Although the authors do not name and advocate a specific alternative, they do note that modern tech offers more flexible ways to manage consent.

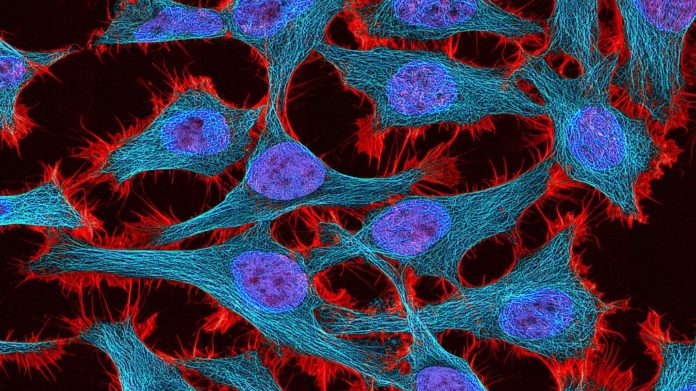

Biobanks: Libraries of human tissues samples

Biobanks store thousands of tissue samples taken from people of all demographic backgrounds and medical dispositions. They link up tissue and genetic information with health and other types of personal data, providing far more clarity and detail to scientists. This is all in the name of biomedical research – particularly genomics and personalized medicine. The potential impact has been described as not only essential, but revolutionary.

Some 500,000 people were recruited by the UK Biobank in a period of just four years, but support for these enterprises is tentative because of the consent issue. Emerging social trends such as biorights campaigns and the involvement of industry risk undermining these repositories via distrust, litigation, and consent withdrawals. Worse still, high-profile cases of database security being compromised by hackers has made participants think twice about involving themselves.

Give me back my genes!

Biorights refers to the idea that participants should have a financial share in these projects and retain authority over what researchers can do with their samples. The authors attribute this growing perception of the right of control to media hype and exaggeration. But as co-author Blake Murdoch argued elsewhere, the idea that genetic information is uniquely valuable is disputable in the first place.

Simply put, genetic variation is measured according to variation in the DNA sequence of our genomes, although differences are very minimal: we are 99.9% similar according to the National Human Genome Research Institute. When it comes to analyzing tens of thousands of samples taken from the wider national population, the uniqueness of an individual’s contribution is therefore extremely minimal.

Each individual’s contribution is not unimportant however, because it is the tiny differences across large sample numbers that provide researchers with the precious data they’re after. So this begs the question, should people be allowed to claim a stake in these ventures despite how little unique genetic information they offer? If so, how could biobank ventures compensate everybody without completely sinking the project and ruining the opportunity to make discoveries which can save lives?

It’s those corporate monsters, man….

Trouble really starts to stir when the commercialization of health products comes into play. This is an inevitability, as the success of biobanks depends greatly on public-private partnerships and the subsequent chain of investment, development, and distribution.

A 2016 study found that 68% of participants were happy to provide blanket consent to biobanks, but that figure drops down to 55% when commercialization and profit is on the table.

“Understanding public perception – particularly around concerns – is important,” says Caulfield, who has written before about public perception and why it should not drive policy. “It can inform policy development, but it shouldn’t be the sole driver of policy. For example, if consenting to research can be viewed as a right, then you can’t use public perception to alter an existing policy.

“Even if 80% of the public feels comfortable with a new consent approach, that still means 20% wants specific consent, which isn’t insignificant. All it would take is a few individuals to stir controversy.”

For all the investment and work put in to biobanks, these projects will continue to walk on shaky ground until we have a consensus on consent. Allaying the fears of the public while remaining consistent with the law will be crucial when composing this policy cornerstone.