After two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, wearing face masks in public to reduce viral transmission has become a new normal for many of us. And while it likely won’t come as a surprise that face masks impact our nonverbal communication — and affect our ability to recognize faces — a new study from McGill University has explored just how significant this impact is.

The study was led by Sarah McCrackin, a postdoctoral researcher in the Laboratory for Attention and Social Cognition at McGill University, and published in Social Psychology.

How do face masks impact nonverbal communication?

“One of the most important cues we receive from faces is facial expression, which signals the individual’s emotional state,” explained McCrackin and co-author Jelena Ristic, a Full Professor and Willian Dawson Scholar at McGill, in a press release.

“With the sudden and widespread adoption of face masks in 2020 to curb the COVID-19 pandemic, we set out to investigate how covering the lower part of the face with a mask impacted our ability to recognize basic emotions.”

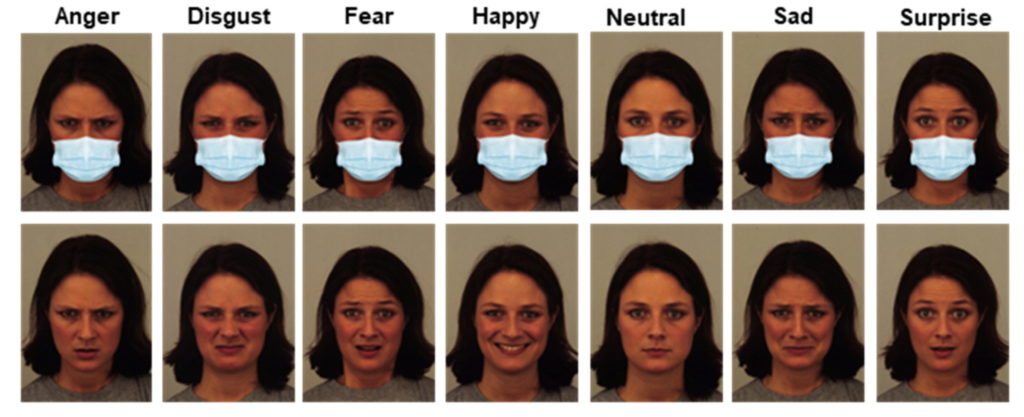

To do this, they carried out a survey where participants were shown photographs of faces with happy, sad, fearful, surprised, disgusted, angry, and neutral expressions. Half of the photographs were photoshopped to include face masks. Study participants were then asked to identify the emotion in each photo.

After carrying out their survey, the researchers found that all emotions were more difficult to recognize when the face was masked. Overall, masks impacted recognition accuracy by about 24%.

When they considered each emotion individually, however, the team also found that these results were not the same across emotions. Disgust and anger were the most difficult to recognize — with accuracy affected by 46% and 30%, respectively — while participants were only 10% less accurate at identifying fear when the faces were masked.

The team went on to consider whether certain people were better at identifying masked emotions than others. After surveying the study participants on their personality traits, they found that those with altruistic personalities were better able to identify emotions.

They also found that those with more extroverted personalities were slightly worse at identifying emotions than those who were introverted. This was slightly surprising, as extroverts have previously been shown to be associated with high emotion recognition. However, the authors theorize that extroverts may spend more time looking at a person’s full face, meaning that important cues were missing from the masked images.

How can we express ourselves when masked?

Face masks are likely here to stay, and going forward, these results will help us understand the impact they have on our communication. This is particularly important in settings such as hospitals or classrooms, where masks must be worn for prolonged periods of time.

“[D]octor-patient relations require easy interpretation of emotion states for better patient outcomes,” McCrackin and Ristic said.

“Anger and sadness are two emotions that commonly come up when dealing with difficult medical problems, and our data suggest these emotions are two of the most impacted by masks.”

The authors suggest that FDA-approved transparent face masks may be a helpful option for these settings.

Nonverbal cues are just one mode of communication, and it’s important that we find ways to express ourselves when these cues aren’t fully available.