One of the biggest changes felt by most of us during the COVID-19 pandemic has been the transition to working from home in an effort to adhere to social distancing protocols. For many, this means a switch from in-person interactions to hours spent in online teleconferences — often through the increasingly-popular video conferencing platform Zoom.

We trust platforms like Zoom with our work-related communications and files — but should we? A new report from the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab investigated the security of Zoom meetings, finding significant weaknesses in cases where confidentiality is needed.

Significant security weaknesses

To investigate the video conferencing platform’s confidentiality, Citizen Lab senior research fellow Bill Marczak and senior researcher John Scott-Railton listened in on internet traffic associated with Zoom meetings hosted on Windows, Mac, and Linux computers.

They found that although Zoom does encrypt its voice and video content, the encryption scheme used isn’t up to industry standards.

“Our research showed that Zoom had relied on a non-traditional encryption scheme that they developed themselves — never a recommended idea for any application, let alone one that is used extensively by governments, business, and civil society,” explained Ronald Deibert, professor of political science at the University of Toronto and director of the Citizen Lab.

“After reverse engineering Zoom, we demonstrated that the encryption included flaws that could allow a clever hacker to intercept Zoom’s audio and video.”

In documentation for the platform, Zoom previously said that it uses “end-to-end” encryption. This is an encryption scheme that aims to prevent data from being read by anyone aside from the sender and receiver (the “ends” of the communication).

Communications that are end-to-end encrypted must be decrypted by a set of cryptographic keys that outside parties don’t have access to. This means that any third party accessing the communications — for example, an Internet service provider — will only be able to access it in an encrypted form.

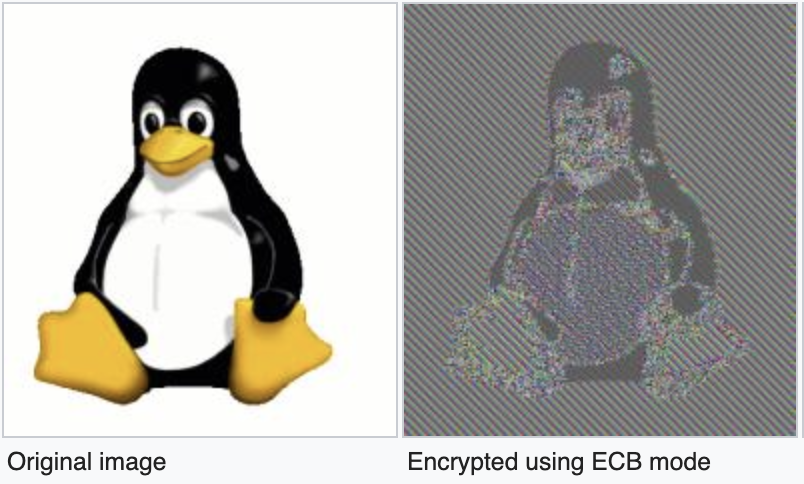

The specific type of end-to-end encryption Zoom claimed to use is known as AES-256, and is the strongest encryption standard available. But after looking through the internet traffic associated with test Zoom calls, Marczak and Scott-Railton realized that this wasn’t the case. Instead, they found that Zoom was using a much less secure encryption standard that is known to preserve patterns in the data being communicated.

Marczak and Scott-Railton also found that cryptographic keys being generated for encryption and decryption during Zoom calls were routed through servers in China, regardless of where the meeting participants were actually located.

This is worrisome, because cybersecurity laws in China aren’t the same as those in Canada. Zoom may be legally obligated to provide these cryptographic keys to authorities in China.

“This risk is quite serious, and means that hypothetically China’s security agencies could surreptitiously insert themselves into any Zoom call,” said Deibert.

Zoom “not suited for secrets”

In addition to the serious security flaws mentioned above, Marczak and Scott-Railton discovered a worrisome issue with Zoom’s Waiting Room feature, which allows users to control when participants join a meeting.

Their report currently refrains from disclosing the nature of this vulnerability in an attempt to prevent it from being abused by ill-intentioned hackers. However, the researchers are in talks with Zoom about patching the issue, and have noted that Zoom has been responsive. Zoom has also recently released a response to the research, acknowledging the responsibility they have to keep meetings secure in a time when so many are relying on their platform.

For meetings that require strict privacy and confidentiality — for example, governments concerned about cyber espionage or healthcare providers handling sensitive patient information — the Citizen Lab warns against the use of Zoom.

“As much of the world moves into work-from-home rules and self-isolation, technology has become an essential lifeline,” said Deibert. “Applications and systems that were originally designed for more banal uses have all of a sudden vaulted into areas of life and work for which they were never designed, including confidential communications, sensitive and classified government deliberations, and interactions among high-risk groups — including health workers and their patients.

“It is imperative that researchers subject these applications to close security in the public interest.”

As for the rest of us? According to Marczak and Scott-Railton, we don’t need to worry too much.

“For those using Zoom to keep in touch with friends, hold social events, or organize courses or lectures that they might otherwise hold in a public or semi-public venue, our findings should not necessarily be concerning,” they said.

But regardless of how secure you need your meetings to be, it’s always a good idea to keep yourself informed about safety online. The Citizen Lab’s Security Planner is a free, online tool designed to improve your online safety with personalized advice from cybersecurity experts, and is one way to get started.