It may be hard to believe, but the United Kingdom is becoming even cloudier and rainier. Worse still, the dreary weather might be behind the apparent country-wide resurrection of rickets, a childhood disease that results in bone deformities and disability.

In most developed countries, rickets is categorized alongside diseases like polio or leprosy – devastating illnesses of the past, eradicated, or nearly so, by modern science and medicine. By the mid-1900s, scientists had revealed that rickets was primarily caused by vitamin D deficiency and that changes in diet, ultraviolet light therapy, or simply more time spent outside in the sun could decrease risk.

Eventually rickets turned into a rarity in the developed world, appearing only in places where sun exposure is severely limited. Here in Canada, for example, cases of rickets tend to cluster in Nunavut, Yukon and the Northwest Territories, the northern half of the country where year-round sunlight is diminished.

But over the past couple of decades the incidence of rickets has nearly doubled among British children. Before the recent resurgence, the disease had been on the decline since at least the 1960s. So, what is behind the new surge of rickets cases in the country? Is the already notoriously sunless UK becoming even cloudier?

A duo from the University of Toronto, Haris Majeed and Dr. Kent Moore, think so. They believe the pattern can be explained by an obscure climate phenomenon, the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. Their conclusions were published last week in Scientific Reports.

The AMO is a naturally occurring climate process that results in small changes in sea surface temperature in the North Atlantic. Every 60 to 80 years, the AMO causes a shift in sea surface temperature, oscillating between slightly warmer and slightly colder. Coincidental with these temperature shifts are changes in sea level pressures, which ultimately result in changes in cloud cover and precipitation.

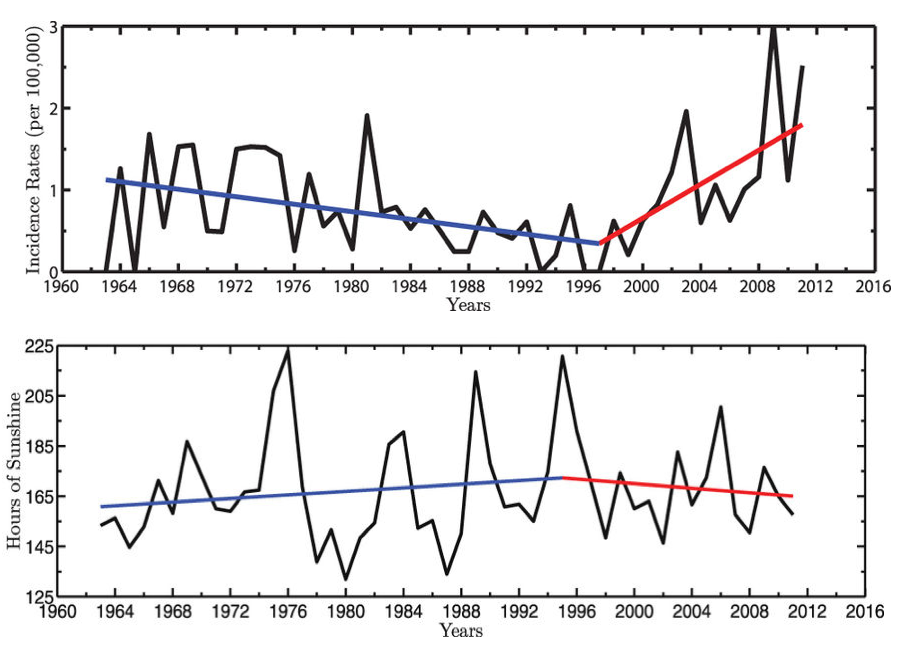

During the period of rickets decline in the UK – the early 1960s to the mid-1990s – the AMO was in its positive phase of slightly warmer sea surface temperatures, which Majeed and Moore show led to a drier period for the country and increased year-round hours of sunshine by about 2.36 hours per month each decade.

In the mid-1990s, however, the AMO oscillated into its negative phase, resulting in increased cloud cover and fewer year-round hours of sunlight – a net loss of roughly four hours per month each decade.

When you map the periodic cycling of the AMO-induced sunlight changes against the incidence rates of rickets, the correlation is hard to ignore. The changes in hours of sunlight over time are almost a perfect inversion of rickets incidence rates, with the incidence rates falling as sunlight increases and vice versa.

Majeed and Moore propose that, while other factors are likely in play, such as changes in children’s diets and different diagnostic practices, the periodic cycling of the AMO can partly explain the recent surge of rickets in the UK.

The duo believe that when it comes to population health, “environmental and climate related phenomena often seem to be ignored”, but their findings illustrate that sometimes understanding disease pathology requires a much broader perspective.

It will be another 15 to 25 years before the AMO cycles back into a negative phase, and brings back more sunshine and drier weather to the country. Until then, the researchers expect to see a continued increase in rickets incidence across the UK.