This event was part of the ArtSci Salon. Stay tuned for more events exploring the intersection of art and science.

On Oct. 20, science and art enthusiasts gathered at the Fields Institute for Narrating Neuroscience: a discussion on the role of storytelling and art in communicating complex and often abstract concepts in neuroscience. The four speakers each presented their perspective on neuroscience communication, painting a diverse and multifaceted picture. Art can help explain neuroscience concepts and sometimes, neuroscience can even dictate art.

Matteo Farinella, PhD, Presidential Scholar in Society and Neuroscience – Columbia University

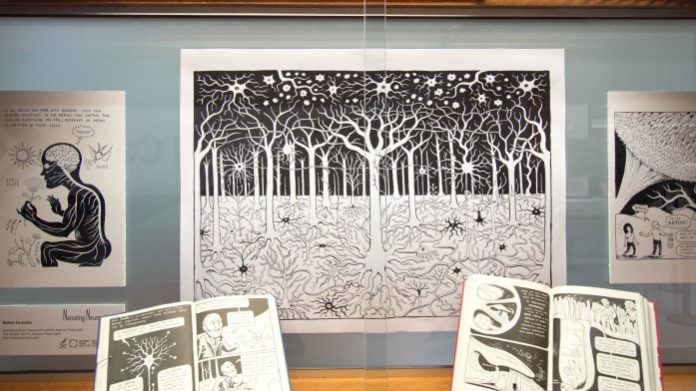

Matteo Farinella has two passions in life, neuroscience research and comics. He never once considered that the two could be combined, until a post-doc named Hana Ros joined his lab. She saw the potential, and what started out as an inside joke between the two of them soon became a beautifully illustrated story called Neurocomic. Supported by the Wellcome Trust, Neurocomic is a graphic novel journey through the human brain.

Farinella’s goal was not to try and write a textbook in comic form – good textbooks with beautiful illustrations already exist. Rather, he wanted to focus on the narrative component. In his story, the main character gets trapped inside a brain and must learn about it to find his way out. Throughout the story, this main character can act as a surrogate for the reader, asking questions and making comments that the reader might have.

The success of Neurocomic surprised Farinella and part of his current work as the Presidential Scholar in Society and Neuroscience at Columbia is figuring out exactly what made it so successful, so that it can be repeated and taught to other science communicators. He believes it might have to do with the personal factor in neuroscience. It’s easy to see neuroscience and medicine as relevant, because everyone has a body and a brain.

Shelley Wall, AOCAD, MSc, PhD – Assistant professor, Biomedical Communications Graduate Program and Department of Biology, UTM

Shelley Wall is a certified medical illustrator with a PhD in literature and a Masters in biomedical communication. Maybe it was this combination of qualifications that drew her to comics about medicine.

Similar to Farinella, Wall’s work focusses on the narrative component, but rather than being purely educational, Wall is interested in more of a memoir-style comic where patients and caregivers share their personal experiences. When someone is diagnosed with a serious neurodegenerative disease, they are rarely interested in the mechanism or history behind the condition; they want to know what kind of treatment they can get, how long they have, and what effect this will have on their family.

That’s where Wall thinks memoir-style comics can help. Seeing someone’s journey through the same condition can help the patient feel less alone, while answering all those sensitive questions. Wall is also motivated by her personal experience being a caregiver for someone with early onset Parkinson’s.

Alfonso Fasano, MD, PhD, Associate Professor – University of Toronto Clinician Investigator – Krembil Research Institute Movement Disorders Centre – Toronto Western Hospital

Fasano’s presentation was unique, in that it didn’t focus on using art to communicate neuroscience, but rather on how neuroscience, more specifically brain disorders, can affect art.

Fasano showed examples of artists diagnosed with Parkinson’s and how their art changed before and after diagnosis, and also after starting a medication regimen.

He also explained that patients on Parkinson’s medication can sometimes develop a condition called punding, where they are compelled to perform a task, seemingly a form of art, over and over again. One patient insisted on painting every appliance in her house.

Although Parkinson’s medication can increase what Fasano called “creative drive”, he doesn’t truly believe these patients became artists if they weren’t artists before. To Fasano, a true artist also requires a certain amount of skill and talent that he doesn’t believe medication can falsify.

Tahani Baakdhah, MD, MSc, PhD candidate – University of Toronto

Baakdhah’s presentation was different not because of the topic, but because of the medium. Baakdhah is the talent behind Knit-A-Neuron Toronto, where she teaches participants how to crochet various types of brain and retinal cells using homemade patterns. You may have seen her colourful and cuddly creations on Instagram or Twitter.

Baakdhah, who is completing her PhD in retinal stem cell biology at the University of Toronto, says she loves how engaged people become at these types of events. They knit and chat about neuroscience, including the role of the cells they are creating. Many people take their projects home and finish them at a later date.

If you’re close to U of T campus and interested in seeing more art meets neuroscience, check out the passageway between Bahen and Koffler, where the Narrating Neuroscience guerilla exhibit is on display.