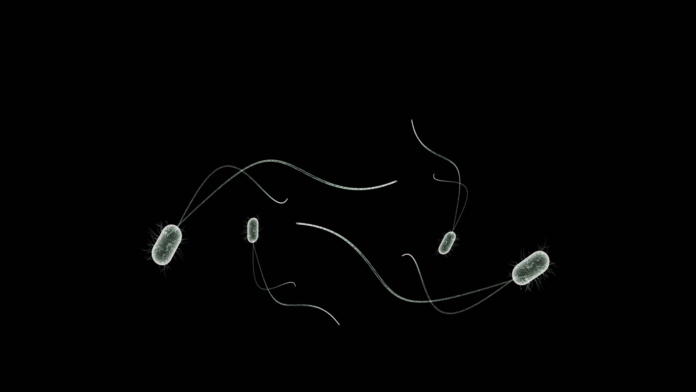

The antimicrobial properties of silver have been used in medicine for thousands of years. Silver ions punch holes in bacteria and once inside they bind to DNA, putting critical functions at risk. But creating a silver-based coating to keep bacteria off medical devices has proven to be a formidable challenge.

That’s why researchers at the University of British Columbia and Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute screened a library of dozens of chemical components to find a more promising solution. Their study was published in ACS Central Science.

The main challenge in developing a silver-based coating is silver’s toxicity. It acts against bacteria in a more potent way than it does human cells, but nonetheless, too much of this poison causes side effects in patients.

Secondly, existing formulations require complex steps to form a coat, and they don’t stick very well to devices or implants. That means they’re not very durable, and proteins and crystals also tend to gum up their surfaces.

Lastly, they rely on bacteria coming in direct contact with the coating to have an effect. That means that bacteria die right at the surface of the devices, and as that biomass builds up, the devices get clogged and lose effectiveness.

The research team settled on a new formulation that tackles all of these issues by releasing silver in small, controlled amounts over time. They incorporated silver nanoparticles and dopamine into a blend of two non-stick, water-loving polymers that prevent direct contact of human cells with the silver nanoparticles before the silver ions are released. The formulation readily coats surfaces in one step, and it repels bacteria and other unwanted materials to keep the device clean.

As the silver ions are slowly released, they create a local area around the device that defends against bacteria that could cause an infection. Direct contact between the bacteria and the device is no longer required.

The researchers exposed their coating to a mixture of hard-to-kill bacteria, and even after a month they didn’t find any bacterial adhesion. Implanted into rats for a week, they observed that anti-biofilm activity was maintained in vivo, and they also found that their coating was highly biocompatible.

Because so little silver is needed for this coating, not only does it reduce the likelihood of silver toxicity for patients, it would also add only 50 cents to the cost of manufacturing a catheter.

“This is a highly effective coating that won’t harm human tissues and could potentially eliminate implant-associated infections,” said co-author Jayachandran Kizhakkedathu, professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the University of British Columbia, in a press release.

“It could be very cost-effective and could also be applicable to many different products.”