There is renewed global interest in long term space missions, but we don’t yet know how to stay healthy in zero gravity.

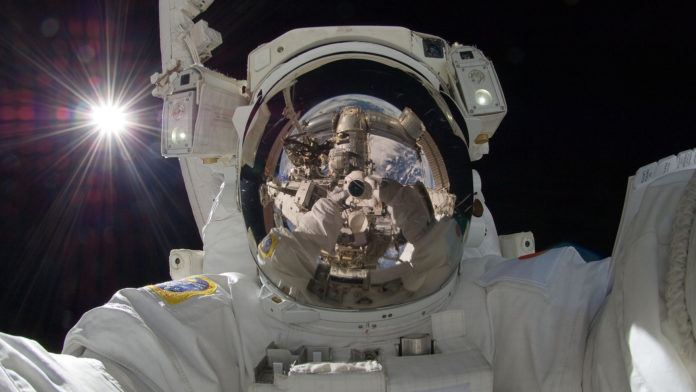

Astronauts feel weightless during spaceflight and on board the International Space Station (ISS), which perpetually feels like cresting the top of a hill on a fast roller coaster.

One of the pressing health concerns is that astronauts seem to age more quickly in space. Richard Hughson, professor of kinesiology at the University of Waterloo, works with Canadian astronauts on board the ISS to monitor how their arteries and circulatory systems change during spaceflight. They use ultrasound and collect blood samples during their mission.

Hughson then compares those data to measurements taken from senior residents living in a long-term health facility, where they can be monitored at home instead of in the artificial conditions of a laboratory.

He found that in the span of six months in space, astronauts experience artery stiffening equivalent to 20 years of aging on Earth.

Arteries normally stiffen with age, but this can lead to many health conditions, including heart disease, insulin resistance, stroke, and diminished cognition and movement.

Astronauts exercise daily, but they still lose so much muscle mass on space missions that they require months of rehabilitation to regain their pre-flight strength after landing back on Earth. In addition to the changes in artery stiffening, blood flow in general is also thrown off in zero gravity; blood and other fluids wind up distributing more into the chest and head.

Bone marrow, the home of blood cell production, is also affected, with suppression of white blood cells that mediate immune responses to infections and enlargement of fat cells.

These physiological changes make a compelling case for developing artificial gravity devices for spaceflight as a countermeasure.

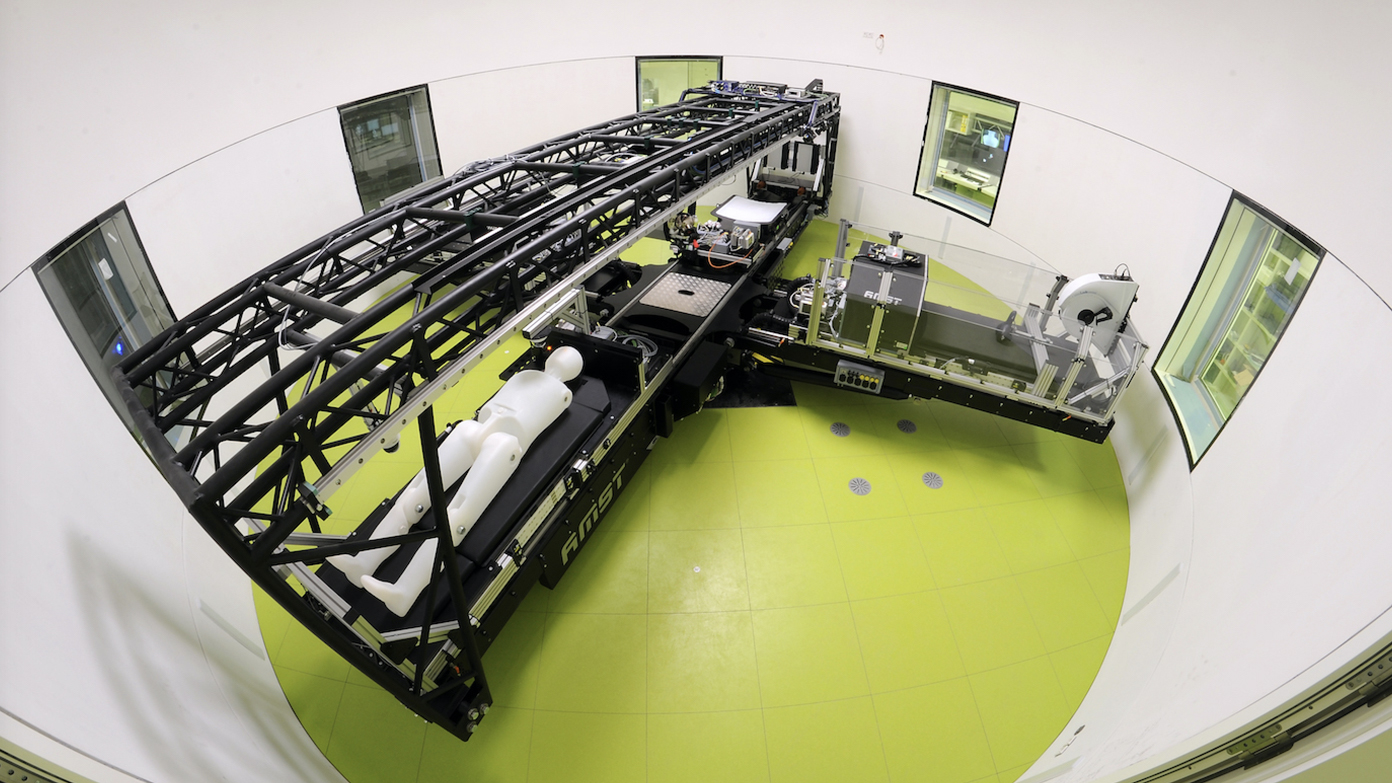

One possibility is a human-sized centrifuge: a spinning device with arms that extend outwards like an overhead fan. A user can lie down on one of the arms, feet pointing away from the centre. The centrifugal force during spinning applies an outward force that simulates the effects of gravity.

Ottawa physician Dr. Guy Trudel is one of the researchers testing a short-arm centrifuge in the :envihab facility in Cologne, Germany.

The centrifuge is equipped with ultrasound to take a look at a user’s heart in real time. It can simulate gravity up to six times the natural force on Earth, and users can exercise during operation. The researchers can also record and monitor a user’s movements through video.

This research aims to learn the best ways to counter the extreme environments of spaceflight. For instance, body position in the device may matter, and the best exercises for a healthier outcome still aren’t known. Researchers can also probe into how long an astronaut should spend in an artificial gravity device each day, and whether the equivalent to Earth’s gravity or hypergravity would work best.

And the countermeasures that might work in space may also illuminate possible treatment programs on Earth. Understanding the changes that happen both in aging and in spaceflight could point to overlaps, where options that lead to reversals in each help solve the same problems in the other.

Artificial hypergravity devices could counter negative effects of spaceflight, but they may also help rehabilitate patients after a long confinement to bedrest after a surgery or serious illness. They could also be efficient countermeasures to conditions like osteoporosis or muscular atrophy.

While there’s no place quite like home, there may be many actions we can take to bring its health benefits with us in spaceflight. These same technologies may also play a role in staying healthy without ever leaving the ground, and that’s good news for all humankind on Earth and beyond.