As the notorious Zika virus ran riot in South and Central America throughout 2015, the U.S. was on high alert to monitor, catch, and contain a domestic outbreak. But it turns out that by the time the alarm was finally rung in July 2016, Zika had already been sneaking about for months, infecting hundreds of people.

A landmark study by scientists from Canada and several other countries tracked the transmission of the virus and traced its route into the States. They estimate that Zika might have been floating around unchecked since the spring of 2016.

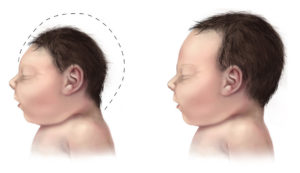

This infection spreads not only via mosquito bites, but also through sex, blood transfusions, and crucially, from a pregnant woman to a fetus. From there, congenital Zika syndrome leads to congenital disabilities such as microcephaly, where the brain and head don’t develop correctly.

Microcephaly can produce an intellectual disability, dwarfism, poor motor function, speech difficulties, and seizures. Most tragically, however, it often results in stillbirths and miscarriages.

Genomic fingerprints

Little was known about the transmission of Zika because clinical samples of it contain only specks of genomic information. As such, it’s hard to track.

For this study, which comprised three separate papers full of research, scientists sequenced over 200 Zika genomes sourced from infected people or the mosquitoes themselves. Using these data, the team could chart Zika’s spread across the States, Brazil, and other South American nations.

The researchers believe that between four and 40 introductions of the virus triggered and contributed to the outbreak in Florida that year. A total of 256 confirmed cases across four counties were reported, nearly all of them focused in south-east Florida.

The study highlights Miami Beach and neighbouring districts like Wynwood and Little River as a hotspot: 47% of all infections were acquired here, and a total of 241 cases came from the wider Miami-Dade County alone.

So how did it get to Miami and beyond? The team’s data pointed the finger at high traffic volumes going back and forth between the Caribbean, a region that was already known to be suffering multiple outbreaks.

To date, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recorded 5,399 cases in the States, with 5,127 in travellers returning from contaminated areas.

Mosquito menace

A particular sub-species, Aedis aegypti, is the primary type of mosquito responsible for unleashing the Zika virus. These pests also carry dengue virus and chikungunya virus, and both are nasty, fever-inducing illnesses that have no direct cure; only the symptoms can be treated.

Despite that, just 1 in 1,600 of A. aegypti mosquitoes carries Zika. They make seasonal advances into Texas and Florida, triggering what are now occasional and isolated cases of the virus.

Canadians need not worry, though, we can still be world travellers – Zika’s symptoms are mild but recognizable. If you are travelling in an area with a Zika warning in place, be on the lookout for headaches which progress to bloodshot eyes, rashes, and possibly a fever.

The Zika threat has diminished considerably since the height of the epidemic, but cases are still emerging in the West and beyond. This research contributes to our understanding of how the virus initiates transmission into a new region. The authors note that future outbreaks in Florida are likely to be something of a cyclical event, dependent on the transmission dynamics of Zika-heavy areas such as the Americas and the amount of traffic flowing back and forth.

Here at home, don’t anticipate an A. aegypti invasion anytime soon. This subspecies may have been discovered venturing north to a small extent, but they ultimately can’t handle the winter and lack the numbers to inflict serious damage. Instead, we Canadians should keep our anxieties focused on lyme disease and West Nile virus.