Fragmented sleep may lead to worse cognitive abilities in older adults with or without Alzheimer’s disease, according to University of Toronto researchers.

The team examined 685 adults older than 65 who were participants in two large studies in the US, around 265 of whom had Alzheimer’s disease. During their analysis, researchers took into account the participants’ sleep patterns and performance on cognition tests, and also examined samples of their brain tissue following death.

Frequent waking in the night was linked with changes in microglia, a type of immune cell in the brain whose role is to fend off pathogens and clear away the organic waste left over after a cell dies. In turn, these changes in the microglia, such as accelerated aging and other abnormalities, were linked with declines in areas of cognitive function like memory and reason.

“There are two important takeaways from this paper,” said co-author Andrew Lim in the UofT press release. “One is that poor sleep is associated with brain immune dysregulation or dysfunction. The second part is that that dysfunction appears to be further associated with impaired cognition.”

The study builds on previous research linking poorly functioning microglia to bad sleep and cognitive decline. Quality sleep is believed to be an essential part of the brain’s process of removing toxic beta-amyloid proteins that accumulate in the brain in Alzheimer’s disease.

‘Youthful’ microglia may help prevent cognitive decline

Participants in the study were monitored using FitBit-like devices which can pick up on subtle signs of waking. The devices were worn for 10 days in a year for an average of two years. Participants were also subject to annual cognitive tests and agreed to donate their brains for study after their passing.

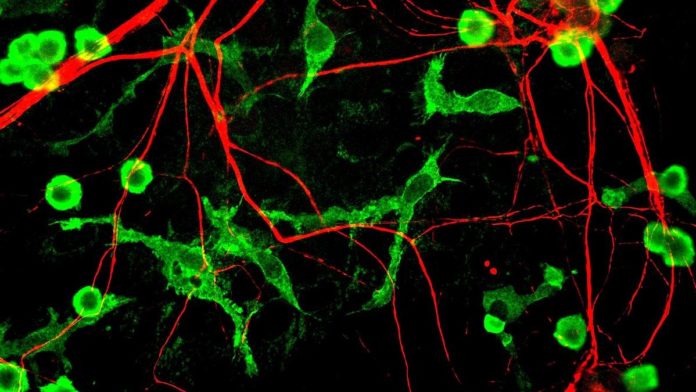

There were two ways in which the researchers were able to examine the microglia. Firstly, the appearance of activated microglia is distinct from unactivated ones, so researchers were able to identify them and measure their density and proportion. This was performed under the microscope using the brains of deceased persons.

Next, using genetic sequencing, the researchers looked for patterns in gene expression among the microglia. This allowed them to differentiate between “older” and “younger” microglia, the ages of which are determined according to levels of activity.

Putting it all together, researchers found the thread they had hypothesized. Frequent wakers with or without Alzheimer’s had a higher volume of activated microglia and gene expression patterns indicative of older microglia. In turn, these poor sleepers also performed worse on cognitive tests.

“Those in the study who had better sleep had ‘younger’ and less activated brain immune cells, and this was relatively protective against the negative effects of Alzheimer’s disease pathology on cognition,” says Lim.

Lim commented to the Globe and Mail that people wrongfully assume that “bad sleep is just part of aging, and it’s something that’s annoying but to be tolerated, rather than aggressively managed or aggressively investigated.

“This adds one more reason to take sleep [problems] seriously and to look for your treatable causes and to address them.”