Video games can be incredibly engaging, keeping players coming back for the thrill of levelling up. This playful motivation is the foundation of a growing trend of gamification in physical therapy.

Motion-based games were brought into the mainstream by the Nintendo Wii, a game console that features virtual versions of sports like boxing, tennis, and baseball. Instead of pushing buttons, players simply swing their arms as they would in real life.

Building on this concept, researchers at the Project Engineering and Research Lab (PEARL lab) in Toronto are customizing motion-based video games for children with cerebral palsy (CP). Movements in these games mimic the exercises performed in physical therapy by CP patients.

Marrying the engagement of video games with the practical need for therapy helps keep patients moving. The problem with conventional therapy is that it’s fairly dull and can even be painful; getting kids to bother with it is a challenge. Not only do they need therapy to improve motor function, but they also need a healthy level of exercise to keep fit.

So, what if motion-based video games could be used to entertain and motivate the kids through a therapy session? A scoreboard, competition, and lots of bright colours and sounds are a lot more fun than hospitals, exercise mats, and ropes.

Video game physiotherapy has already shown great potential

A 2013 study explored the efficacy of interactive computer play as a form of motor therapy for individuals with CP. The report found “promising trends on upper limb motor function in individuals with CP are evident as motivating, enjoyable, and barrier-free options for engagement, participation, and therapy.”

Dr. Darcy Fehlings, Senior Clinician Scientist at Holland Bloorview Hospital, was the lead author of this paper. She works on a motion game project separate to the PEARL lab called Exergames.

“In our research we’ve shown that [motion-based video games] can facilitate cardiovascular fitness, so we get their heart rates up to the moderate level of heart rate and physical exertion,” says Fehlings. “We’ve also shown some improvements in perceived physical health and quality of life.”

“Children love to interact with computer games, so rather than using that as a negative, we’re trying to capitalize on it as a potential positive effect,” adds Fehlings.

Similarly, a 2010 study looked at the potential of telerehabilitation on adolescents with severe hemiplegic CP. Virtual reality video games were installed in the homes of three participants who used a special glove to exercise finger movements and interact.

Over the course of three months, playing 30 minutes per day, five days a week, all participants showed improvements in extensions, lifting, and grabbing with their weak hand.

Making physical therapy as rewarding as it is demanding

The best games are near-perfect examples of Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s theory of ‘flow’ — experiences that are as demanding as they are rewarding.

Flow is the psychology of optimal experience: a state of total involvement, where creativity runs fluidly when we are at the height of our game. Some examples include an improvising musician or an athlete at peak performance.

To achieve flow in these games is especially challenging as players need to overcome difficult and painful tasks to play.

The PEARL lab also plans to tackle problems such as affordability, location issues, game difficulty, cheating, safety, and engagement all at once. Of course, that’s incredibly ambitious and raises a lot of questions.

How do we know the kids will like these specialized games as much as mainstream ones? How do we target specific areas of the body that need therapy? Let’s start with what CP is and how conventional therapy works.

How to regain the power to move those muscles

CP is a neurological condition that affects patients’ motor functions, and it varies widely in its severity according to the sub-classification the patient lives with. There are three leading causes of CP: neurological diseases, traumatic brain injuries, and genetic disorders.

The idea behind conventional therapy is to generate neuroplasticity, the brain’s remarkable ability to repair damaged neural connections through brain training.

Exercising the function that the connection is responsible for improves neural communication, resulting in goals like steadier arms, flexible legs, and precise finger movements.

In other words, one’s brain is doing some proverbial weight lifting and getting stronger. This rewiring of the brain is a cruel master, however, as it demands dedication, focus, and repetition.

“Practice is key for neuroplasticity to occur. It’s just like any other motor learning task: if you don’t practice, you’re not going to improve,” says Ajmal Khan, research engineer and manager of the PEARL lab.

Not only that, but it also needs to be meaningful and for the patient to have a strong will driving their rehabilitation.

“They really need to be actively engaged in the practice, and it needs to be meaningful to them,” says Fehlings. “It needs to be repeated and built over time so that the skill level can advance and engage the child.”

The lovechild of physical therapy and video games is born

Naturally, the kids hate conventional therapy; it hurts, it’s annoying, and they have to endure hospital waiting rooms after a day at school. As for parents, imagine working full-time jobs and then driving out to some far away location where expensive specialists treat an understandably reluctant child.

What if there were a way to minimize the burden of travel and waiting rooms while keeping up commitment and progress? Enter the Home Virtual Reality Therapy (Home VRT) System.

After safety and basic efficacy were established via a perspective study using the Nintendo Wii, the PEARL lab noted some glaring issues:

- Wii games weren’t specific enough with their exercise movements, and the difficulty was often beyond the capabilities of kids with CP.

- For some kids, however, cheating was easy because the game doesn’t discern between dominant limbs and weaker ones.

“It’s hard to find games that target specific movements and have an accessible level of difficulty,” adds Khan. “So that’s where we got the idea of ‘hey, why don’t we create our own video game?’”

CP is a spectrum, so these new games needed to accommodate that factor. A group of occupational and physical therapists who worked alongside the PEARL lab were able to identify the types of motion games with therapeutic value.

“Based on that, the guys made game prototypes and then got feedback from the therapists on what ways we could improve,” says Khan.

“What we’ve found is that it’s hard to make a single game that will please everyone because to design a single game that will work for all kids is very difficult; it’s a spectrum,” adds Khan. “The full assemblage will target anyone, but certain ones are may be more simple.”

The ability to cheat undermines the whole point of therapy

Kids are kids. They want to win, simple as that.

“The Wii was the first exposure for most as regards playing games while moving, but it’s hard to make it therapeutic because if the kids want to cheat, they will.”

Kids can cheat by using their dominant limb instead of their weaker one to win the game. Why would a kid swing, punch, or throw with their weaker limb when they can get more points using their dominant limb?

As such, the team had the challenge of integrating an equivalent to constraint therapy — a way to ensure the child uses the correct limb for the therapeutic exercise.

In a healthy brain, the contralateral (or opposite) side controls the corresponding hand; that is, the left brain controls the right hand, and the right brain controls the left hand. But take, for example, a child who has suffered damage to the left side of their brain: in this case, the brain compensates by shifting control of the right hand over to the right side of the brain.

With constraint therapy, therapists can drive activity back into the contralateral side and improve hand function. This is as literal as it sounds in conventional therapy. Kids often have their dominant limb restrained in some fashion, for example, an arm wrapped in material similar to a cast so they can’t grab things with their hand.

Customized video games can achieve the same result in a less invasive way. The technology is sophisticated enough that points can only be scored by using the appropriate limb for the task at hand.

It’s user-friendly to change this in the options section of the game menu — a parent can easily tell the game what limb should be focused on. An invaluable feature for kids who need to exercise multiple body parts.

Restoring motor function through music and flapping like a bird

The Home VRT system possesses a wide array of mini-games that appeal to children in a variety of ways. Some of the more artistically inclined games include musically oriented tasks, where children reach for different instruments to make a song.

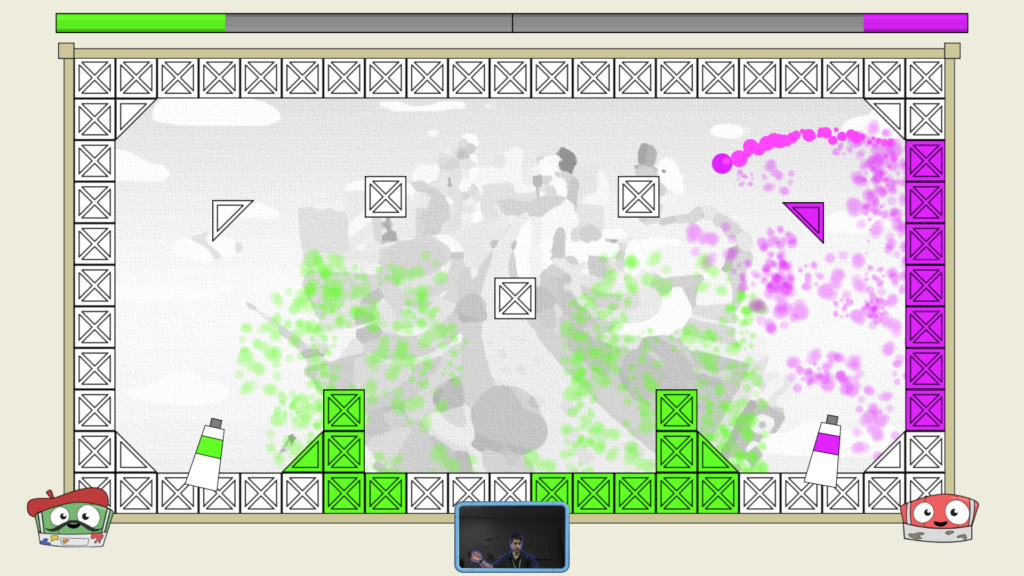

‘Warpaint’ adds colour and design to the mix, allowing children to create pretty pictures while swishing their arm as if they had a brush in hand. For those more interested in exploration and task-oriented games, there’s an open-world one in which the child flaps his or her arms to make their avatar, a bird, fly.

The player’s avatar can be customized and upgraded, but you need to put in the work and earn those points first. “As you play the mini-games you have a daily prescription by the therapist, and as long as you play as much as you’re meant to, you get rewarded with coins which you use to buy items,” says Khan.

The system has been a hit with parents and kids at the hospital, and now parents are asking how they can get one into their home, which is the team’s ultimate goal. “That’s the key benefit, in the home, to get kids to practice,” says Khan.

Completely replacing traditional therapy was never the plan, but having a reliable tool to keep up practice between conventional therapy sessions is hugely positive. If the kids enjoy it so much that they forget that what they’re really doing is therapy, everyone is a winner.

Peddling on modified bikes for points and fitness

Improving motor function is only one side of the coin. Like all other kids, children with CP need to exercise and keep up their fitness regimen.

Since 2012, Fehlings has pursued her patch in this burgeoning field of research by focusing on fitness games. Her team uses a stationary bike that has been modified specially for individuals with CP — it’s fitted with pedal straps, lateral support and a seatbelt.

The bike is hooked up to a game, and the on-screen avatar gains more power according to the effort put into cycling.

Not only that, but kids can compete with friends in multiplayer mode in person or over live chat. If the abilities of both kids differ significantly, there’s a balancing algorithm built into the software to even the playing field and encourage competition and fun.

The target audience for Exergames is teenagers because growth spurts during puberty lead to complications with CP, making mobility more difficult.

“Because physical mobility is challenging for them, they often have trouble maintaining physical fitness, and there’s this whole burgeoning literature about how important physical fitness is, but for these individuals, it’s particularly important,” says Fehlings. “In teenage time, if your physical abilities become more limited, it can also create more social isolation.”

Here’s the catch: it simply won’t ever compete with mainstream games

It all sounds brilliant, but there are limitations of course. The “sad reality of it”, according to Khan, is that popular platformer games such as Super Mario and the multitude of first-person shooters are impossible to appropriate because they’re just too hard to play.

Peers and rival media pose threats to the success of the project in their own way. If the kids with CP are watching their friends zip fluently through Minecraft and Lego Batman, they might feel patronized having only simpler games available to them.

“If any kid were going to pick between the two, they would probably pick from the mainstream,” he adds. “But the idea is, you’re doing therapy now, so maybe it would be easier if it’s a video game.”

Nonetheless, the kids are finding them fun enough to get lost in, and they care less about the pain and difficulty of the exercise and more about beating that level. Quintessential flow psychology in action.

“That’s the motivation factor of the design with these games, they should be just challenging enough that you have to make some extra effort to succeed, so it’s that regular sort of extrinsic reward cycle,” says Khan.

Virtual Reality Therapy appeals to adults as well

Games aren’t just for kids, after all. If you’re not convinced, Vera Fung might be able to change your mind. She’s a researcher at Sunnybrook Research Institute, also in Toronto, and has published work exploring the use of the Nintendo Wii in rehabilitation.

Her 2012 study on total knee replacement surgery outpatients found that the Nintendo Wii has potential as an adjunct to regular therapy, especially for balance and lower extremity function.

Previous to this research, she conducted a prospective study involving occupational therapists and physical therapists, who were mostly in favour of using the Wii for burn victims. Both groups of therapists cited the potential for pain distraction, increased motivation, and improvement in motor function deficits.

It’s reasonable to assume that video game therapy wouldn’t appeal to adults, but Fung disagrees. She believes that the increasing role that technology plays in our lives has helped people become more comfortable with the idea of using it in something like therapy.

But more than that, what really attracts people to it “is if they are innately competitive, as they want to achieve the objective, they want to best their opponent.”

Indeed, the stereotype that video games are a past time for kids has long been debunked. The average age of a gamer is 35, and females make up a significant and growing portion of the audience — over half by some estimates.

As for the Nintendo Wii, it opened up new demographic segments to the market through its universal popularity and greater accessibility.

Pain is an issue that knows no age boundary, and games offer a unique opportunity for patients to minimize it during therapy sessions. “Someone that has a lot of pain does very well with Nintendo Wii fit cause it distracts them away from what they’re focusing on in a way that’s interesting and fun,” says Fung.

Even surgery teams are using virtual worlds as a form of pain distraction. It works by overwhelming the senses and undermining how much attention the brain can pay toward the pain. In therapy, this is invaluable, as it expands the limits of what the patient can achieve in a session.

Therapy will remain a long, hard road regardless

Video game therapy is no miracle cure, but it definitely has the potential to become a regular tool in the therapist’s arsenal.

Engagement and cooperation are some of the biggest problems therapists face, especially with children. Integrating a medium that appeals to kids into the process is enormously helpful.

Khan says it’s still early days and that this could all go any which way in the future, although both he and Fung commented that commercial entities such as Electronic Arts have declined to help publish or invest in the area.

Markets aren’t what’s important, though. It’s creating wider distribution nets so greater numbers of people can benefit from these innovations.

“I don’t see it taking over, but I’m excited by the opportunities that it will provide,” says Fehlings. “The kids really enjoy it, so that’s what keeps us motivated.”