You can’t necessarily pick and choose where endangered species grow and thrive, so conservationists need to think creatively to provide solutions.

A lot of land that is home to rich biodiversity is also privately owned. Financial incentives could encourage conservation efforts by these private owners to help Canada meet targets set forth in its international treaty agreements.

One proposal led by researchers at the University of British Columbia seeks to shift tax burdens to owners of land with lower conservation value to generate the revenue needed to launch this reward program. Spreading out this cost over many land owners would enable a modest estimated increase of only 0.13% to 0.51% in their property taxes to cover the cost of conserving 17% of Canadian terrestrial ecosystems.

Canada is obliged to reach this conservation target by international agreements put together at the 2010 Convention on Biological Diversity. Although we have until 2020 to achieve this, current projections suggest we are falling short.

We’ve seen this all before, right?

Tax relief programs are nothing new in the world of conservationism. At both a federal and provincial level, different governments have worked out agreements and contracts with land owners to protect green spaces or endangered species across the country.

Examples include the Federal Ecological Gifts Program, an exchange of income tax benefits for charitable gifts of private land. In Ontario, there’s the Ontario Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program – a 100% reduction in property tax on land areas maintained to protect “provincially important natural heritage features.”

Some mutual back scratching indeed.

The trouble is that land can be very expensive, and it’s simply not practical to go around with such a slippery chequebook. Deals must be sought to meet the land owner halfway.

This could mean protecting one secluded area of someone’s land, such as a forest, or a water body, in exchange for a certain percentage of tax relief.

The picture becomes more complex when you consider that land owners might incur further losses from losing access to parts of their land. Perhaps they farm it or mine it for resources, but regardless, they won’t be able to continue their activity if it’s under protection. Same goes for the government. Conservation management is a running process that needs continuous funding and resources, so the costs don’t stop after the initial purchase.

Got Georgia on my mind

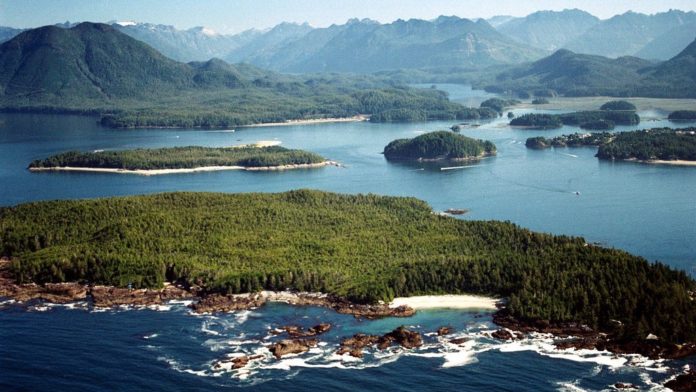

The Georgia Basin region is not only a hotspot of biodiversity, but of real estate as well. The average hectare will set you back $5.2 million, so there’s not a hope of buying these people out.

Nonetheless, this is a prime spot to study the efficacy of their approach. The team examined a 2,250 km² area of Coastal Douglas Fir, where less than 10% of oak woodlands and ≤0.3% of old forest (250+ years) that existed before European colonialism remain.

Prior to European disturbance, Aboriginal land management practices that benefitted hunting and foraging created a bountiful environment for ecological growth. The average age of a Coastal Douglas Fir tree then was over 300 years old.

In spite of how degraded the majority of Coastal Douglas Fir in this area now are, they are still home to 117 species at risk of extirpation. Besides the old forest itself, there are wetland focal bird communities, maritime meadow plant species, and red-listed Douglas Fir sub-species in need of protection.

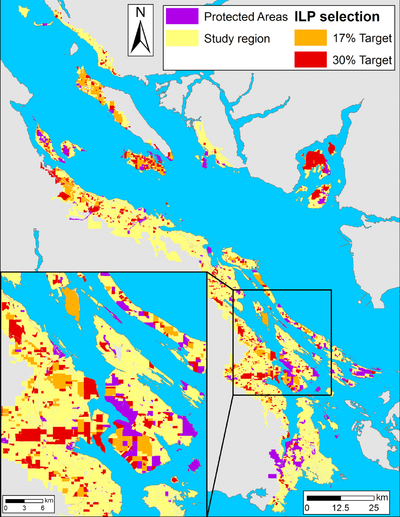

Researchers used data provided by the Coastal Douglas Fir Conservation Partnership to outline a strategy with conservation level projections of either 17% or 30%. The result would depend on different scenarios that entail various degrees of tax relief and corresponding increases elsewhere.

Parcels and tax presents

Out of a total of 198,058 sites in B.C.’s Georgia Basin region, the annual combined tax intake is estimated to be $2.32 billion. These patches of land are known as ‘parcels’, and the researchers prioritized them regarding their conservation value. A total of 1,188 parcels in this area are already under federal protection.

Scenario one proposes that eliminating tax on a further 464 high conservation value parcels would help to achieve the 17% target. The cost shifted to owners of low conservation value parcels would see an increase of between 2.1 and 4.2 cents per $1,000 of land – a 0.13% to 0.27% rise.

Scenario two has grander ambitions – a 30% conservation target piggybacking on a tax increase between 0.7% and 1.4% on low conservation value parcels. This would cover the estimated 16 to 32 million dollars spent in tax relief.

These figures are based on the theoretical assumption of a 100% level of uptake by HCV land owners, which would be next to impossible to achieve. To be more realistic, the authors split the data to outline different rates of uptake: maximum (100%), optimistic (50%), and typical (25%).

Even with the more pessimistic uptake of 25%, conservation goals could still be met by including 861 parcels of varying conservation value. In this case, a tax increase ranging from only 0.13% to 0.51% is all that’s needed.

The authors admit there are holes in the paper, such as the threat of biodiversity loss and the use of average regional tax rates. Further study is required to hammer out any pesky variables, but this is still a highly useful study that governments the world over could use as their conservation template.