A Canadian fish fossil discovered in Miguasha has unveiled fresh insights into the evolution of human hands via fish fins. The discovery, a result of a collaboration between Australian and Canadian researchers, may reveal the missing evolutionary link in the fish-to-tetrapod transition.

Millions and millions of years ago, during the Devonian period, fish started to move into habitats like shallow waters. The fossil record shows us that around the time of this transition, there was an enormous diversity among fish. Those that could adapt to the land could exit this highly competitive environment and make use of the abundant resources for food and shelter.

The development of limbs facilitated the evolution of tetrapods (four-limbed creatures like humans) who progressed to the land, making this transition one of the most significant evolutionary steps in history.

The mystery surrounding the details of this transition has made it one of the fundamental problems of evolutionary biology.

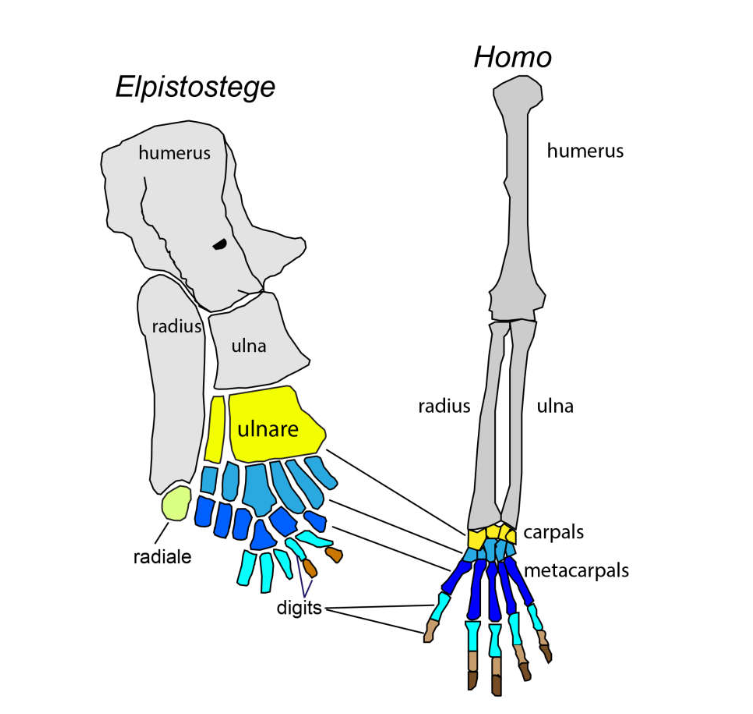

Several questions remain unanswered, including the timing of when vertebrate hands and feet developed. Now, this 1.57 metre-long Elpistostege fossil provides the first evidence that the bones of the modern human hand and forelimbs of most modern animals first developed in fish.

Elpistostege is a type of lobe-finned fish (Sarcopterygii), which is a class of bony fish. They are characterized by their fleshy pectoral and pelvic fins that articulate with the pectoral and pelvic girdles using a single bone. This is the first known elpistostegalian fossil from this period to retain the pectoral fin in totality.

“This is the first time that we have unequivocally discovered fingers locked in a fin with fin-rays in any known fish”, said John Long in the press release. “The articulating digits in the fin are like the finger bones found in the hands of most animals.

“This finding pushes back the origin of digits in vertebrates to the fish level, and tells us that the patterning for the vertebrate hand was first developed deep in evolution, just before fishes left the water.”

Previous papers claimed to have found digits in fish fins, but these turned out to be irregularly shaped bones, explained Long to the Jerusalem Post.

“Elpistostege further blurs the line between fish and tetrapods in showing a greater number of tetrapod novelties than are present in any other ‘fish’,” say the authors.

Elpistostege: the closest we get to a ‘transitional fossil’

As described in the paper, Elpistostege was a large predator that lived in estuarine habitats circa 380 million years ago. Their powerful fangs meant they may have survived on various types of other elpistostegalians, which can be found fossilized in the same deposits.

Until now, most elpistostegalian fossils were incomplete, making this new find the most valuable yet. The specimen takes the crown from the Tiktaalik, a closely related elpistostegalian known only from incomplete fossils found in Arctic Canada, which was previously believed to be the closest known link.

“Elpistostege is not necessarily our ancestor, but it is closest we can get to a true ‘transitional fossil’, an intermediate between fishes and tetrapods,” said co-author Richard Cloutier in the press release.

Looking forward, Long said the team hope to explore the fossil’s skull, braincase, and other structures of the head in search of other evolutionary advantages which may have helped the migration to land.