Although COVID-19 vaccines have now been approved for use in Canada and the end of the pandemic finally looks to be within sight, the effects of COVID-19 will undoubtedly linger in our society for many years to come. For example, many doctors predict that face masks and vigilant hand-washing will become the “new normal” even after vaccinations have been administered to the majority of the population.

But if you’ve started to notice just as many face masks on the ground as you have on actual faces, you’re probably not alone. Personal protective equipment, or PPE, is beginning to emerge as a serious source of plastic pollution in cities around the world, due in part to the fact that many people are unaware of how exactly to dispose of it.

To better understand this new environmental contaminant, a team of plastic pollution researchers from across Canada carried out a survey of PPE pollution discarded in Toronto. The study was led by Justine Ammendolia, a marine biologist and plastic pollution researcher, and published in Environmental Pollution.

PPE is an emerging source of plastic pollution

Ammendolia started noticing PPE pollution early on in the pandemic, and quickly realized that she needed a systematic way to track all the different items that were being discarded.

“We’d spot a facemask here, a disposable glove there, and it becomes a pattern over the course of days where we’re not able to keep track of all this new litter that’s popping up that’s related to the pandemic,” Ammendolia said in an interview. “It was just alarming how quickly it was starting to build up and accumulate.”

Fortunately for Ammendolia, a citizen-science tool called the Marine Debris Tracker seemed to be ideally suited for her needs.

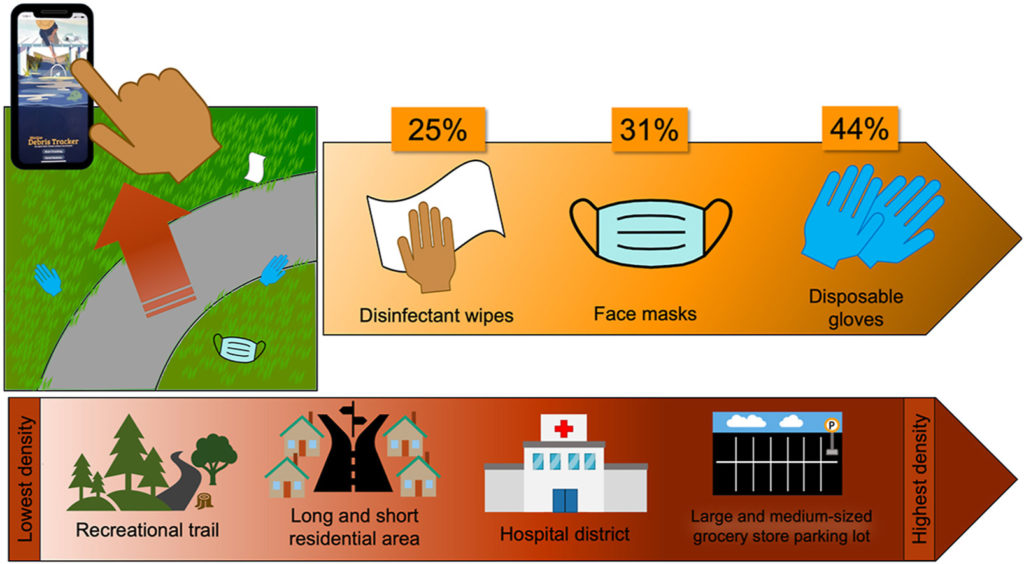

While the tool was originally developed to track pollution around waterways, Ammendolia and her colleagues were able to adapt the tool to track disposable gloves, face masks, disinfecting wipes, and other PPE-related refuse, pinpointing the exact location where each item was found. These functionalities are still available in the app, meaning that anyone with a smart phone can participate in the citizen-science project and track PPE pollution in their own neighbourhood as well.

Ammendolia’s initial survey was carried out in six different regions in Toronto, including both residential and commercial areas. This allowed them to study a wide range of human activities, shedding light on which activities in particular may be leading to greater PPE pollution.

Disposable gloves are the worst offenders

In total, the team recorded 1,306 different items throughout their survey areas. They found that disposable gloves were the most commonly discarded item, representing 44% of their total survey. The highest density of items was recorded at a large grocery store while the lowest density was recorded on a recreational trail.

PPE pollution is a hazard to both the environment and our health, and the authors make a number of recommendations about how to deal with this new source of pollution going forward.

They suggest that policymakers encourage hand-washing over the use of disposable gloves, and direct efforts towards raising awareness on how to properly dispose of PPE. Masks and gloves are not recyclable, and can in fact pose a health risk to waste management staff if they’re not properly discarded.

To this end, the authors also recommend modifying the types and locations of waste bins around the city. Several locations they surveyed did not have touch-free waste bins available, and members of the public may be wary of having to touch waste bins while the pandemic is still ongoing, opting to litter their used PPE instead.

Going forward, Ammendolia hopes that similar studies can be carried out in other locations around the world.

“We created the project being socially relevant in Toronto, but then we’ve actually asked our colleagues around the world to highlight it,” said Ammendolia.

“The goal is really to map it out in a structured way where we understand where it’s likely to end up so that we can better inform policymakers.”