Narwhals are notorious for being some of the most elusive mammals in the sea, which makes studying and helping to conserve them no easy feat. But with the help of a video camera designed to pick up on infrared light, a team of researchers from the University of British Columbia and the University of Manitoba has gotten a rare view of these so-called unicorns of the sea.

The investigation was led by Katie Florko, a PhD student at the UBC Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, and published in Ecosphere.

Infrared cameras have long been used to study animals because these cameras have the ability to pick up on body heat. This makes them useful for spotting animals that might otherwise blend in with their environments, which is why Florko and colleagues initially set out to observe polar bears and other Arctic animals with an infrared video camera aboard an airplane.

While they’d hoped that they might be able to spot a few narwhals as well, they weren’t counting on it. Narwhals don’t spend much time above the surface, and they’re known to be skittish, with even distant airplanes often scaring them away. And because water absorbs some wavelengths of infrared light, the cameras Florko and colleagues were using weren’t ideal for penetrating deep under the water.

“Narwhals only surface briefly, so we expected it would be challenging to accurately detect and count narwhals using infrared during our aerial surveys,” Florko explained in a press release.

But to Florko’s surprise, the team was able to spot some narwhals after all — just not in the way they might have expected.

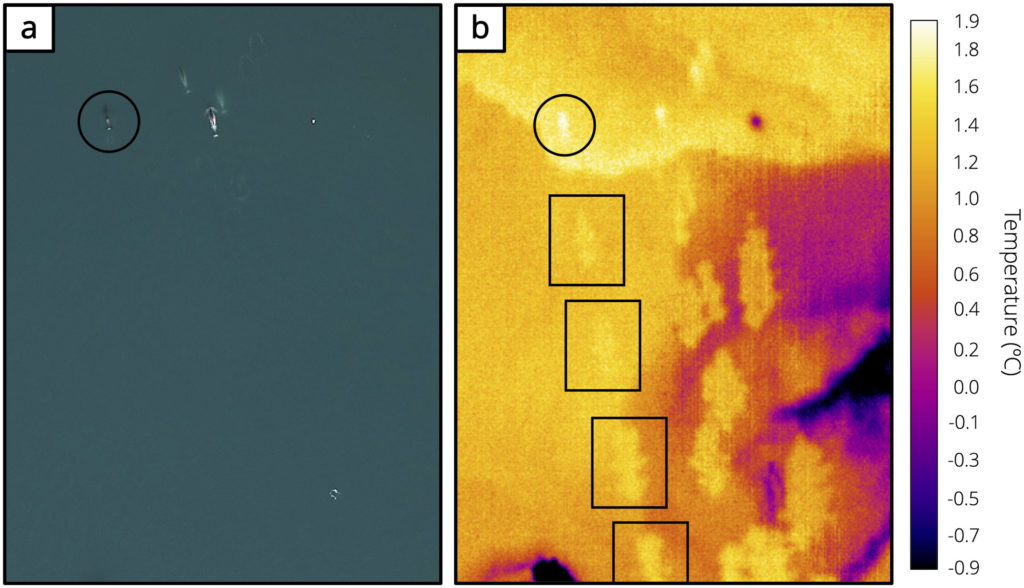

Rather than picking up on the animals’ body heat, the infrared cameras were able to detect their flukeprints: patterns that emerge on the water’s surface caused by motion from their tail flukes. These occur when narwhals and other whale species move through the water and produce turbulence, causing parts of the water to heat up.

Because infrared technology is sensitive to different temperatures, the team was able to spot the patterns caused by these flukeprints as the turbulence brought different temperatures of water to the surface. By monitoring these patterns, the team was able to follow the narwhals as they travelled through the oceans and confirm that it really was them when they eventually surfaced.

Going forward, this technique will help researchers track narwhals as they journey through the Arctic oceans. The patterns can also indicate the direction the narwhals are travelling in, which can shed light on their migratory behaviours.

“Knowledge about Arctic marine wildlife, especially at high latitudes, is sparse due to […] high costs and logistical challenges,” the authors said.

“Given these challenges, it is important for Arctic researchers to use innovative technology and approaches.”