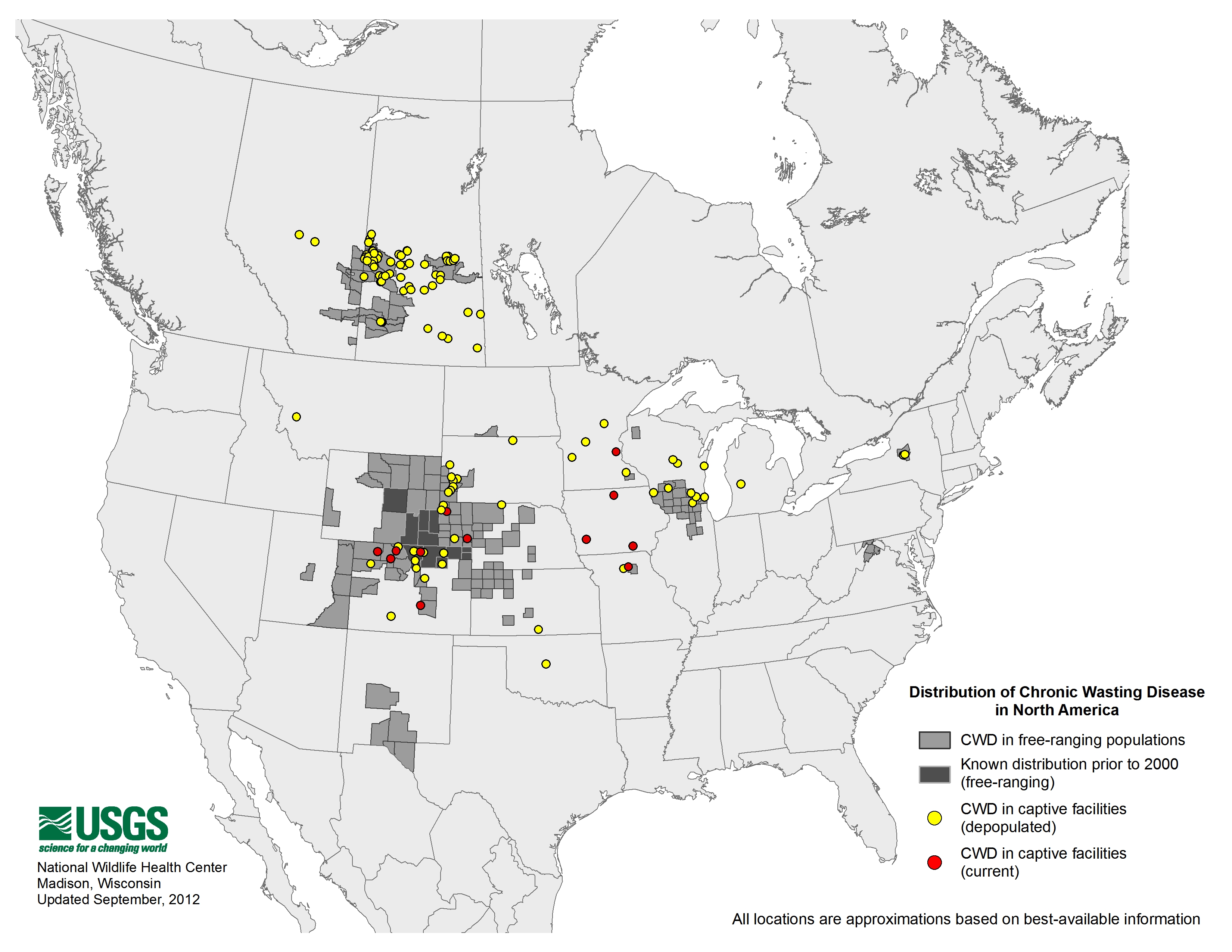

Widespread across North America, Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) is an infectious and fatal neurodegenerative disease that affects creatures such as elk, deer, and moose. CWD has devastated populations of these animals continent-wide, and has also been reported in South Korea, Sweden, and Norway.

The disease-causing agent leaks into the environment through biological fluids like urine, feces, and saliva, or the carcasses of decaying animals. When animals graze on contaminated land, the infection spreads.

The symptoms of a CWD infection include disorientation, lethargy, and an inability to consume food or water properly, ending in a slow, painful death over months.

CWD is a prion disease, which is the same family of diseases as ‘Mad Cow Disease’ (BSE). Unlike most of the infectious diseases we know, which are more commonly are caused by viruses or bacteria, prions are misfolded proteins that influence neighbouring proteins to take on their form. Because protein shape is vital to function, this leads to a cascade of degeneration.

This has understandably got hunters on edge. No evidence has emerged showing that CWD can transfer to humans but the possibility can’t be ruled out – especially considering that Mad Cow Disease led to many human deaths in the 1990s.

Stealthy prions may be negated by this compound

Now, researchers have discovered that an acid found in rich humus soil may help to fight back. Their findings show that it degrades the misfolded CWD prions that cause the disease in the first place, making this compound a friend of the hoofed ones.

Previous work has shown that soil mineralogy can affect the infective properties of prions; they can bind to certain minerals like quartz and remain potent for years. The team’s experiments with humic acid showed that it negates the infective potential of the prions, and this discovery may prevent CWD from spreading altogether.

For the first leg of their research, the team applied a range of humic acid samples to the diseased brain tissue of an elk. The sample concentrations reflected the variability found in the wild.

Researchers observed that the chemical signatures of the prions were borderline erased (~95%) by the interaction when the sample concentrations were high in humic acid. Low concentrations had only a weak effect.

Second, a study group of mice were injected with a mix of humic acid and infected elk brain tissue, while others were injected with a benign mixture.

Results were similar to the elk brain part of the study: higher concentrations created a weaker presence of prion signals. Following a 280-day incubation period, around half the mice with the active mixture showed no signs of disease.

Conservationists may have novel decontaminant on their hands

Although the exact workings aren’t clear, the researchers hope this compound can mitigate the scope of the infection in the real world.

Ideally, humic acid could eventually be used as a decontaminant to protect populations. Alternatively, this could be the basis of a mapping project, aimed at highlighting areas where disease transmission is most likely depending on the concentration of humic acid in the soil.

The next step for researchers, however, is to investigate the interaction between humic acid and soil samples with prion contamination.

“CWD is a significant emerging and fatal disease of deer, elk and moose,” says Judd Aiken from the University of Alberta. “Given it is shed from infected animals into the environment where it can serve as a source of infection, it is essential that we understand the impact of soil and soil components on this unusual infectious agent.”