One of the biggest hurdles for conservationists is convincing independent donors and governments that their money will produce a tangible result.

Previously, there has been little hard evidence that apportioning budgets for the protection of biodiversity works, but a new report has turned that notion on its head.

An international team of researchers have found that the $14.4 billion that countries spent on conservation between 1992 and 2003 slowed biodiversity loss by 29%. They believe that their analysis could be a tool for policymakers the world over as they formulate a strategy for their nation’s conservation efforts.

“This paper sends a clear, positive message: conservation funding works,” says lead author John Gittleman, University of Georgia.

Investment in poorer countries provides the best value

Researchers found that targeted funding had a positive impact in the countries of 109 signatories of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. Some of the avenues for investment in conservation funding include public education, infrastructure such as roads and guard towers for patrols, management of national parks and protected areas, and training for conservation officers.

To assess the outcome of conservation funding by each country, researchers integrated information on biodiversity changes from 1996 to 2008. A cornerstone of the team’s data came from the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species, a record that has tracked the conservation status of species all over the world for 50 years.

Biodiversity changes were analyzed in relation to records on government and non-government spending on biodiversity protection from 1992 to 2003. The time lag between this spending period and the actual study period of 1996 to 2008 was needed to allow time for effects to manifest.

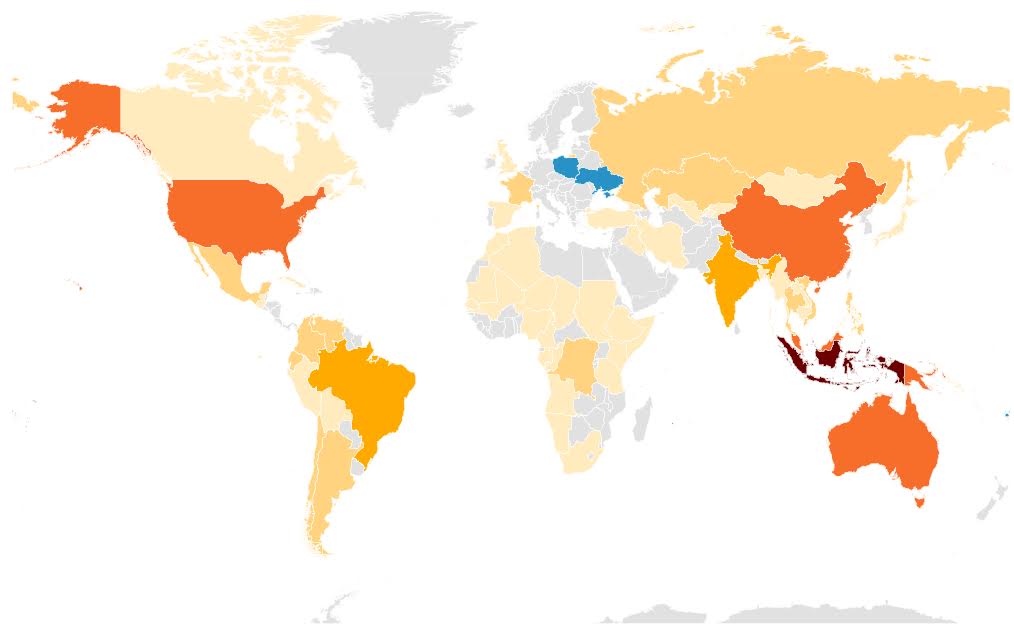

Seven countries comprised 60% of global biodiversity loss in this period: Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, China, Indonesia, India, Australia, and the U.S. (mainly driven by changes in Hawaii).

The presence of Australia and the U.S. via Hawaii on the list is because of the considerable number of unique creatures that exist in these places. There is a bigger burden on these countries, therefore, as there is no ‘Plan B’ for these creatures if they are eradicated.

Domestic investment in Australia has been repeatedly slashed by successive governments, and the country is currently experiencing an “extinction crisis”.

There is a silver lining, however. Indonesia alone experienced 21% of total global loss, but developing countries are home to some of the richest biodiversity spots on the planet, so they offer the best value for conservation funding.

“The good news is that a lot of biodiversity would be protected for relatively little cost by investments in developing countries with high numbers of species,” says Gittleman.

A novel measurement system for biodiversity loss

A key element of the report was a new measurement called the biodiversity decline score (BDS), used to determine a country’s overall biodiversity loss. With this tool, researchers could dig into the records and define the conservation status of endangered species.

“We were able to go back in time with retrospective data and use conservation funding data as the main predictor of the biodiversity decline scores for each threatened bird and mammal,” says Daniel Miller, University of Illinois. “Then we developed a model that accounts for the primary human pressures on threatened species.”

Habitat decline is the biggest threat to endangered species, and the development of infrastructure and agricultural expansion are the main sources of this problem. However, by investing in conservation efforts, the researchers believe that losses can be minimized and human development left largely uninhibited.

“Our model includes a variety of potential threats, but it also includes the counterweight of funding,” says Miller. “Investing in conservation pushes back on the weights that bring biodiversity down by 29%. We were surprised at how positive the finding was. We had a hunch that the funding would be effective, but didn’t realize it would be this effective.”

Armed with hard evidence such as this, conservation lobbyists are in a better position than ever to make their case. For policymakers, this model provides an approximation of value for every conservation dollar spent, so excuses based on a waste of public funds are, thankfully, running out.