Our planet is in the middle of a climate crisis, and the dazzling coral reefs that make up some of the world’s most diverse ecosystems are facing extreme losses as a result.

Coral bleaching events are becoming more and more common, and if global warming levels exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius, the Earth will lose up to 90% of its current coral reefs by the middle of this century. The actions we take to protect the world’s remaining coral reefs need to be strategic, or else these underwater oases may be lost forever.

To address this, an international team of scientists recently undertook the largest-ever study of coral communities in the hopes of identifying the actions we need to take to save them.

The study was led by Emily Darling, a conservation scientist with the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and former Banting postdoctoral fellow in the University of Toronto’s Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, and published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

The largest study of coral reefs to date

Given the rapid progression of climate change, saving all of the world’s coral reefs is likely not possible. Instead, Darling and her team focused on prioritizing the protection of certain reefs that are more likely to be able to survive climate change. These include reefs with key ecological functions, such as fast and vertical growth.

But identifying those coral reefs best suited to conservation is tricky. Comparing different populations of coral reefs requires a large-scale dataset from locations across the world, but no such dataset existed previously.

This is where Darling and her team of more than 80 scientists worldwide came into play. Over six years, the team surveyed more than 2,500 Indo-Pacific coral reefs within 44 different nations and territories. They measured the total coverage of each coral reef, as well as the abundance of different coral types.

They also tracked mass coral bleaching events: devastating incidents where algae get stressed by changes in their environments (for example, temperature increases) and abandon the coral reefs they usually call home.

Algae and coral reefs depend on each other in a symbiotic relationship, providing one another with necessary nutrients to survive. Algae are also responsible for the corals’ bright colours, and when they leave during coral bleaching events, the corals turn completely white. Often, these bleached coral reefs are unable to recover.

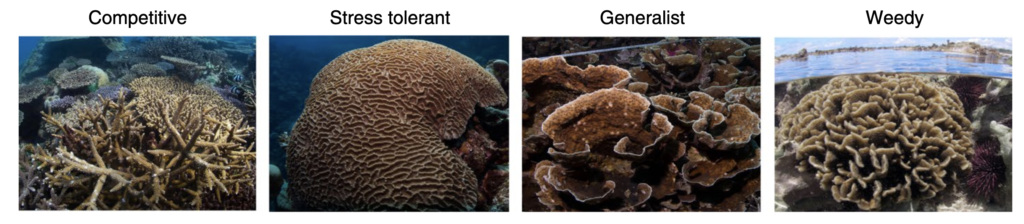

Darling’s analysis focused on four main classes of coral reefs: “competitive” reefs that that can grow complex structures quickly, but that may be vulnerable to environmental stressors; slow-growing “stress-tolerant” reefs that can persist through varying environmental conditions; “generalist” reefs that are typically sub-dominant populations; and “weedy” corals that are fragile and less complex.

In this framework, competitive and stress-tolerant reefs are more likely to be able to manage changing climate conditions, and are thus populations that should be prioritized in conservation efforts.

The team focused on the effects of 21 different social, climate, and environmental factors on the coral reefs they were monitoring. These included human population growth and thermal stresses, among others.

It’s not too late for conservation and recovery

The authors found that the majority of reefs in their sample was dominated by competitive and stress-tolerant populations. This is in contrast to Caribbean coral reefs, which are typically comprised of weedy species, and bodes well for conservation efforts.

“The good news is that functioning coral reefs still exist, and our study shows that it is not too late to save them,” Darling said. “Safeguarding coral reefs into the future means protecting the world’s last functioning reefs.”

Based on these results, Darling and her team came up with a portfolio of three main management strategies for the coral reefs: protect, recover, and transform.

Reefs flagged for protection strategies were those that not only had been identified as competitive/stress-tolerant, but also those which had undergone minimal amounts of bleaching during the 2014-17 El Niño event. This was an unprecedented and extensive global bleaching event caused by rising ocean temperatures that resulted in nearly three quarters of coral reefs in their sample being exposed to fatal levels of heating.

Of the more than 2,500 coral reefs included in their analysis, 449 fit the “protect” criteria.

The recover strategy — which was identified for the majority of reefs in the sample — included coral reefs which had recently been composed of mainly competitive or stress-tolerant populations, but which had undergone devastating levels of bleaching during the El Niño event. The authors suggested that mitigation of local stressors, as well as targeted rehabilitation and restoration programs, could help return these reefs to their pre-El Niño functionality.

Finally, the transform strategy included coral reefs which had been on a trajectory of net erosion even before the devastating El Niño event. For these areas, the authors suggested implementing strategies that would help societies that depend on these coral reefs transition away from their reef-dependent livelihoods.

What can we do to help?

The strategies identified by Darling and her co-authors will help put the world’s coral reefs on the road to recovery, but these alone aren’t enough. Carbon emission levels worldwide ultimately need to decrease in order to protect these unique environments from devastating loss.

“Local management alone — no matter how strategic — does not alleviate the urgent need for global efforts to control carbon emissions,” the authors cautioned in their article. “The widespread persistence of functioning coral assemblages requires urgent and effective action to limit warming to 1.5°C.”

While it may seem hard to affect change as an individual, actions as simple as talking about the climate crisis can have a positive impact. And with any hope, the actions we all take today can help protect our world’s coral reefs far into the future.