When New York resident Katherine Stopa went outside on Jan. 23rd, she knew this wouldn’t be your average snowstorm. “And that’s coming from a Canadian! I couldn’t believe there was already 16 inches and that was only a few hours in.”

In fact, winter storm Jonas dropped almost 27 inches of snow on Manhattan and is considered the 4th worst winter storm in the Northeast in the last 60 years. Many people blamed this year’s El Niño, one of the largest since 1998 and its ice storm.

Rewind to Dec. 24th and you might remember being shocked at the warm weather in many parts of Canada. In Ottawa, temperatures reached the high teens and many dreams of a white Christmas were shattered. Clearly a product of global warming, right?

Actually the relationship between climate change and weather patterns is not so black and white.

El Niño

El Niño is a weather phenomenon that occurs when the ocean water in the eastern Pacific is warmer than usual due to weakening of the prevailing east-to-west trade winds. “This in turn causes massive shifts in global weather patterns, especially in the tropics, but also including more distant regions such as Canada,” says Dr. William Merryfield, a research scientist at the Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis.

Dr. Merryfield develops global climate models that form the basis for Environment and Climate Change Canada’s seasonal forecasts.

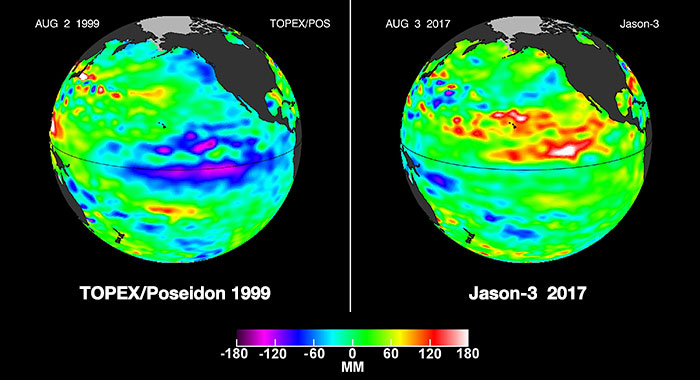

This year’s El Niño was expected to be quite powerful, and according to NASA’s satellite images, sea surface heights along the equator in the central and eastern Pacific were unusually high and very similar to those seen during the monster El Niño of 1997/1998. “This year’s strong El Niño was likely a major, though not the only, factor contributing to the extraordinarily mild temperatures experienced in Ontario and Québec in December,” says Merryfield.

As for Jonas, attributing a single weather event to El Niño is always tricky, but it may have made Jonas more likely to happen. “For example, research showed that the conditions leading to the January 1998 ice storm in Québec and Ontario were more likely to occur when the ocean temperature changes associated with El Niño are present,” explains Merryfield. Similarly, this year’s El Niño may have made it more likely for a storm such as Jonas to occur.

Climate change

Global warming is a phenomenon that is affecting our planet’s climate. The main difference between global warming and something like El Niño is the timescale. “El Niño contributes to large year-to-year climate variations (affecting winter temperatures in Canada for example), whereas warming associated with climate change occurs much more gradually,” says Merryfield. Though our day-to-day weather may not be warmer all the time, the average global temperature has increased by about one degree since pre-Industrial times.

Five-year mean anomaly of surface temperature for 1880 through 2015. Credit: GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP), NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies

However, global warming and weather patterns, like El Niño, may not be unrelated.

A budding relationship

“The warming influences of greenhouse gases will cause warm extremes attributable to El Niño to become more extreme over time,” explains Merryfield. “A strong El Niño temporarily elevates average global temperatures for a year or two. When combined with the general warming of the earth’s climate, this El Niño-induced “spike” can lead to record global warmth,” such as that seen in 2015.

Global warming may also influence the frequency of extreme weather by altering the course of the jet stream directly, although further study is needed to verify this contribution. The jet stream is a fast-moving air current that travels in a gentle wave around our planet, bringing warmer air up from the south and moderating our weather. A recent report in Nature Geoscience studied whether global warming, especially in the Arctic, may have affected the course of the jet stream, producing more marked undulations and loops in its path. Low-pressure areas within these loops can result in extreme weather phenomena like “polar vortices”.

Animation showing the path of the jet stream: a fast-moving belt of westerly winds that traverses the lower layers of the atmosphere. Credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center

Prof. Dick Peltier from the University of Toronto is studying the impact of global warming on extreme weather events, especially as they relate to water resources. By his calculations, the timescale of extreme precipitation events will start being compressed by a factor of 2, meaning they would happen every 25 years instead of 50.

So though it’s easy to blame snowstorms on El Niño and unseasonable warmth on global warming, both could actually contribute to one or the other.