In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic last summer, many Canadians found themselves turning towards biking as a way to get some exercise and fresh air while staying socially distant. And while the environmental and health benefits of riding your bike may be clear, a new study from the University of Toronto has found that biking is also good news for the economy.

The study was led by Bo Lin, a PhD candidate in the Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering at U of T, and published in Transport Findings.

How beneficial were Toronto’s temporary bike lanes?

Throughout the summer of 2020, the city of Toronto installed approximately 25 kilometres of new bike lanes as part of the ActiveTO project, which was designed to help city residents stay active while remaining socially distant. Many of these new bike lanes were intended to be temporary, but cyclists have been petitioning for the lanes to become a permanent fixture of Toronto’s streets in the future.

While Toronto did have a large cycling network even before the ActiveTO expansion, Lin and his colleagues were interested in learning how these new lanes changed — and, potentially, improved — the landscape of biking in the city. Their findings could help influence the city’s decision to keep the new bike lanes going forward.

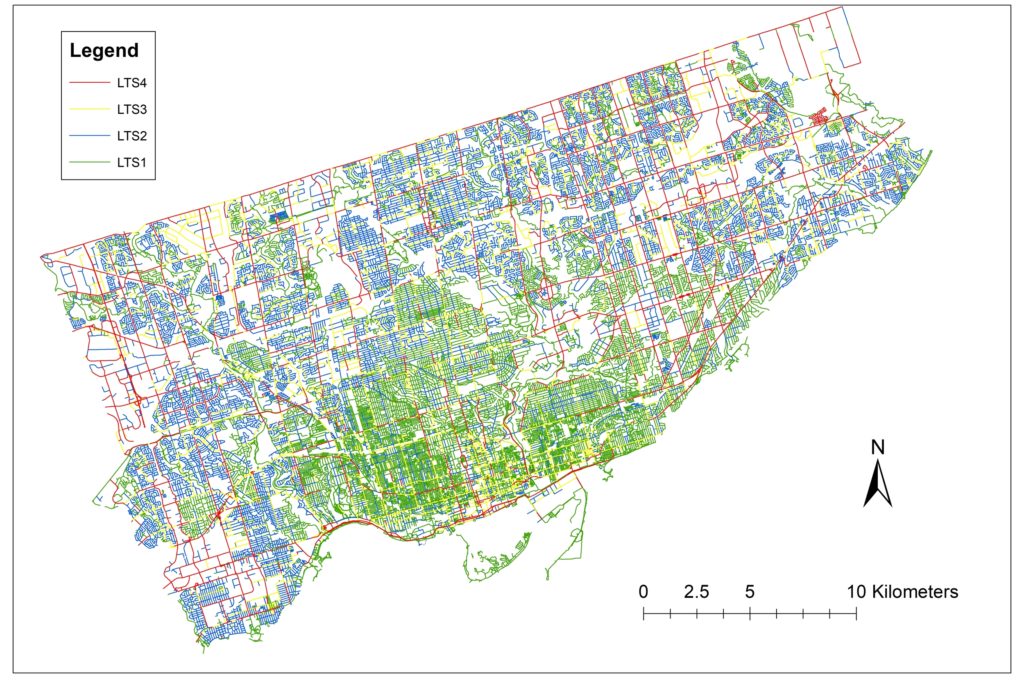

To determine the impact of the ActiveTO lanes, Lin and his colleagues used a metric called the level of traffic stress, or LTS, which they calculated for each section of road in Toronto. A road’s LTS score can range from 1, which represents low-stress roads that are safe for all cyclists, including children; to 4, which covers roads that are only comfortable for “strong and fearless” cyclists.

Their rankings took into account factors such as typical traffic speeds, speed limits, and the type (or absence) of cycling infrastructure present on each stretch of road. Certain types of bike lanes are known to be safer than others, which would lower a road’s LTS score.

Initially, Lin and his colleagues assigned the LTS scores without taking the ActiveTO cycling infrastructure into account. While more than 75% of roads did have LTS levels of 1 or 2, representing roads with low stress levels, the team found that most of these low-stress roads were bordered by those with LTS levels of 3 or 4. In other words, cyclists who wanted to access the low-stress roads needed to brave the high-stress roads first.

The team determined that without the ActiveTO infrastructure, the maximum possible time that cyclists could spend on low-stress roads was only 14.6 minutes. They also found that many workplaces, restaurants, and parks were inaccessible on low-stress roads alone. This is particularly problematic for cyclists outside of the downtown core, who tended to have less cycling infrastructure available, and therefore had to deal with many more high-stress roads on their commutes.

Increased cycling infrastructure led to lower road stress

After factoring in the new ActiveTO cycling infrastructure, however, the team measured an increase in both the maximum travel time and total reachable area of low-stress roads throughout the city. In particular, they noted that low-stress cycling access increased for as many as 100,000 people in central Toronto.

For cyclists located in the north or east of the city, the ActiveTO infrastructure mainly provided increased access to food and parks.

“What surprised me the most was how big an impact we found from what was just built last summer,” said Shoshanna Saxe, an assistant professor in the Department of Civil and Mineral Engineering at U of T and co-author on the paper in a news release.

“We found sometimes increases in access to 100,000 jobs or a 20 percent increase. That’s massive.”

Given that Canadians have lost hundreds of thousands of jobs as a result of the pandemic, and many small business throughout the country are suffering, these findings could help guide economic recovery efforts going forward. With spring finally on the way, cities across the country could focus on improving their cycling infrastructure as a way of increasing access to jobs and businesses.

The impacts were large, but uneven

While Lin’s findings demonstrated overall benefits for the city of Toronto, he noted that these benefits were largely concentrated towards the city’s central, downtown regions. Since many downtown roads were already categorized as low-stress, even small additions to the existing infrastructure made a big difference for cyclists.

While new cycling infrastructure did help the north and east regions of the city as well, the authors note that these regions still have limited links to the downtown core, which is where the majority of jobs and food stores are located.

“Overall, the accessibility impacts of the COVID cycling infrastructure in Toronto were large, if uneven,” the authors said in their study.

Going forward, the team hopes that the ActiveTO infrastructure in the outer regions of the city can be the start of a larger, low-stress cycling network for those neighbourhoods. They also hope that their findings will help guide future decisions about cycling infrastructure in both Toronto and the rest of the country.

“You hear lots of debates about bike lanes that are based on anecdotal evidence. But here we have a quantitative framework that we can use to rigorously evaluate and compare different cycling infrastructure projects,” said Timothy Chan, a professor in the Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering at U of T and co-author on the paper.

“What gets me excited is that, using these tools, we can generate insights that can influence decision-making.”