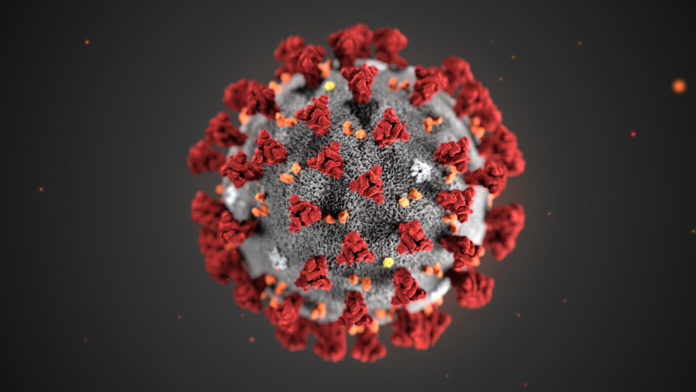

The coronavirus family used to be seen as harmless, usually causing nothing more serious than the common cold. By adulthood, most people have been infected by human coronaviruses multiple times.

But in the past 20 years, the world has seen three major outbreaks of deadly coronaviruses — SARS, MERS, and the novel coronavirus — that made the leap from animals to humans. So what is it about this change that can so often make infectious diseases more deadly and dangerous?

Just like HIV, anthrax, and Ebola, the novel coronavirus is a zoonotic disease: an infectious disease that initially spread to humans from animals. Because they have never circulated in humans before, people have no specific immunity to them.

To make matters worse, the viruses themselves don’t have any experience infecting the human body, either.

“When viruses jump from animals to humans, they can initially cause more severe infection,” said Matthew Miller, associate professor of biochemistry and biomedical sciences at McMaster University, in a press release.

“All viruses care about is continuing to be able to replicate and persist. When a virus jumps from an animal to a person, it basically doesn’t know how to deal with the human body very well and as a consequence it can sometimes make people much more sick than a virus that is a bona fide human virus.”

Usually viruses have a very specific target, infecting only a particular type of cell, and limited to just a handful of closely related species. Genetic mutations can help them jump to a new type of host.

Coronaviruses can more easily gain these species-jumping mutations because they store their genes using RNA, a single-stranded code. By contrast, more complex organisms like humans store their genetic code on double-stranded DNA, where the second strand mirrors the first and acts like a proofreader.

Zoonotic viruses that can infect both animals and humans also have an extra danger: they are even harder to contain because they can spread by the movement of either type of host.

The more humans encroach onto animal territory by deforestation, the more our risk increases. Climate change and globalization are also helping these diseases persist and spread. The human factors at play make it unlikely that this will be the last time a threat like this one will emerge.