Ongoing discoveries about Neanderthals are continuing to reveal a culture that was more rich and complex than previously imagined. We are learning more about everything from their posture to their artistic talent.

Now, research conducted by Canadian and international researchers has unearthed further evidence of symbolic behaviour via jewelry: a hand-carved eagle talon dated to around 40,000 years ago that was shaped into a necklace pendant.

The pendant begs questions about the meaning behind it and broadens the geographic and temporal range that this activity spanned.

In a press release, lead author Antonio Rodríguez-Hidalgo from the University of Barcelona described it as the “last Neanderthal necklace,” since it is dated to roughly the same time they became extinct.

Eagle talons most frequently recorded ornamentation form

Eagle talons are the oldest form of ornamental symbolism in Europe, predating even the perforated seashells used by Homo sapiens in northern Africa.

Previous evidence of Neanderthal experimentation with raptor carcasses extends across the southern regions, with over 20 findings dated between 44,000-130,000 years ago. The Fuamane Cave in Italy and the Krapina site in Croatia are prime examples of this activity.

“Evidence for the symbolic behaviour of Neanderthals in the use of personal ornaments is relatively scarce,” according to the paper. “Among the few ornaments documented, eagle talons, which were presumably used as pendants, are the most frequently recorded.”

The new discovery, which is the first of its kind in the Iberian Peninsula, was made in Cova Foradada (Foradada Cave) near Calafell, Spain. Humans were there up to 38,000 years ago, and some of the last European Neanderthals sought refuge there prior to that.

No Neanderthal remains were found at the site but tools and artifacts linked to the Châtelperronian culture were discovered. Similar tools and artifacts found at sites across Iberia and southwestern France have been linked to this Neanderthal sub-group.

Châtelperronians were among the last Neanderthals and they lived in Europe at the same time that Homo sapiens (modern humans) began to move north out of Africa. In the paper, it is suggested that this practice may have been a form of cultural exchange between the two, as there is no evidence of eagle talon pendants in the African Paleolithic record.

Exact meaning behind such pendants remains unclear

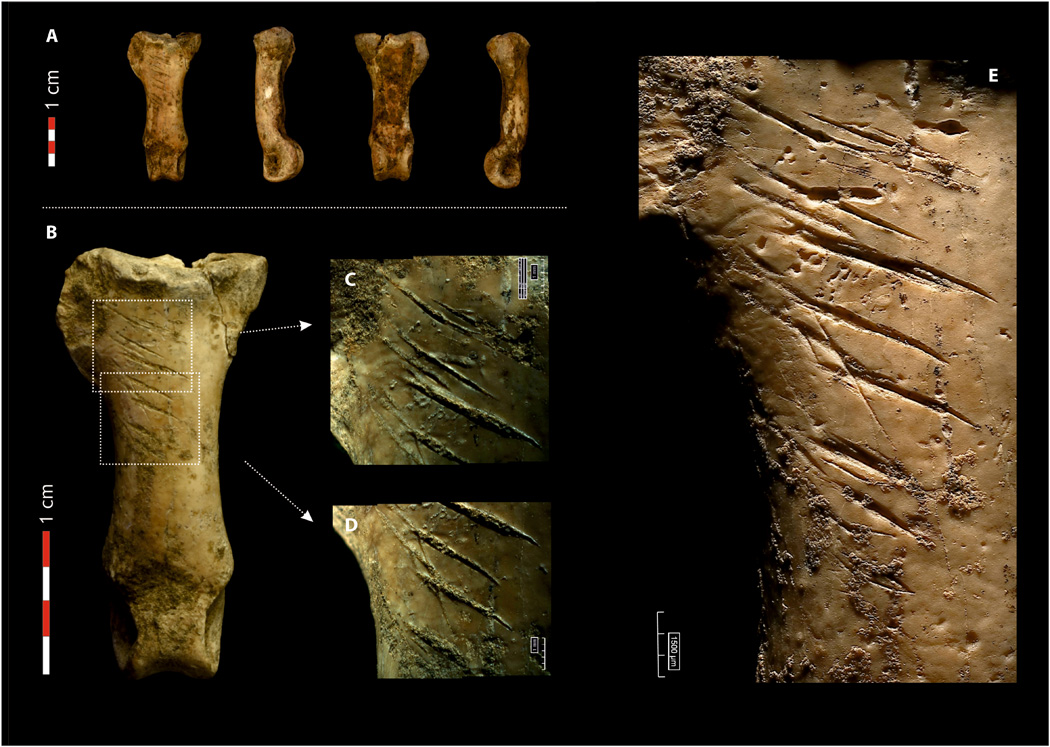

At Cova Foradada, the researchers worked with the remains of a Spanish imperial eagle’s left foot, whose toe bone was riddled with marks inconsistent with animal consumption. The carvings were also analogous with previous findings of eagle talon-based ornaments at other sites.

It’s hard to know just what the Neanderthals saw in the pendants or what meaning they applied to them. It may have meant different things to different subpopulations, but there may also have been a common interpretation across groups.

“Talons of different birds with different appearances and behaviours could transmit different messages about the identity of the bearer,” the authors write. “Our research suggests the presence of a common cultural territory in which the meaning conveyed by these large-raptor talons could probably be recognized by individuals from different groups.”

American anthropologist John Hawks, who was not involved in the study, commented to Smithsonian Magazine that this is further evidence of Neanderthal traditions related to social identification: “Why do you wear ornaments? Why do you go through this trouble? Because you notice something interesting, you want to associate yourself with it, [and] you want it to mark yourself for other people to recognize.”