When then-undergraduate student Teskey Baldwin first found that carnivorous pitcher plants in an Ontario bog were eating salamanders, it was a startling discovery hidden in plain sight.

Algonquin Park is Canada’s oldest provincial park, and its native plants have been observed for hundreds of years. It’s also a popular site for students to do field work. But he had no idea whether it was a fluke or a regular occurrence.

The find may come down to timing, as many previous studies made their observations in spring and summer, but young salamanders transition from living in the water in their larval stage to living on land in the late summer to early fall.

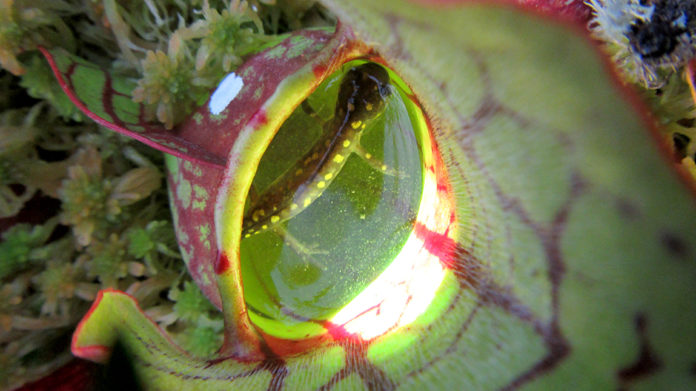

Baldwin, an ecology undergraduate student at the University of Guelph, noted his find in a field report. The following year, Patrick Moldowan, a PhD student at the University of Toronto, made a similar observation and remembered Baldwin’s report. That’s when they teamed up and together they recorded a more comprehensive survey of 58 plants in fall 2018, finding that 1 in 5 pitcher plants had trapped at least one juvenile salamander in their fluid-filled bell-shaped leaves.

Carnivorous plants like these often live in places like bogs, where wet and low-nutrient soil demands alternate sources of nutrition. But most of the time, their diet is almost exclusively comprised of small invertebrates like insects and spiders, with a few exceptions in tropical climates.

Finding a vertebrate-eating plant in Canada was a surprise, and it’s the first such discovery in North America. The frequency suggests that the salamanders are a significant source of nutrition for the plants, with an estimated 5 percent of young salamanders falling prey to the pitcher plants each year. The young salamanders are about the size of a human finger.

The study was published in Ecology.

But the find raises many questions: How did the salamanders, who usually hide under logs or underground, wind up inside these long-stemmed plant leaves? And do the plants actually benefit from this glut of nutrients, or are they overwhelmed?

One theory is that the salamanders, new to land, ironically see the plants as a refuge from other would-be predators. They could be voluntarily entering the trap, later finding that they are unable to escape.

Another theory is that the pitcher plants, having already lured insects, attract the salamanders who are also hoping for a convenient snack. They could then fall in and find themselves trapped.

Their only real chance of survival is a heavy rainfall that could flood the leaves and allow the salamanders to escape.

What happens to the trapped salamanders next is also open ended, as it can take anywhere from 3 to 19 days for the young salamanders to die after they fall prey to the pitcher plants. They might die from exposure to the acidic pH and enzymes that combine with rainwater to create the pitcher plant’s digestive juices. It could also be infection or exhaustion as they swim in a hot bath when the plants bake in the sunlight. They might even starve to death.

From there, it takes about two weeks for the dead salamanders to decompose. This is a risky period for the plants, because if the salamander rots before it can be fully digested, the plant could die. And to top it off, it’s not yet known whether these extra nutrients even benefit the pitcher plants, or whether they would have managed just the same without them. The team plans to study whether catching and eating salamanders actually provides a boost to future growth.

Salamanders are important creatures in the chain that cleans future drinking water, making this significant predator an important one to understand.

This study is a reminder that remarkable discoveries are still waiting in our own backyards, so long as we stay curious and chase those peculiar leads.