During the 2015-2016 El Niño, unusually warm Pacific waters caused droughts, flooding and the worst global coral bleaching event on record. This type of marine heatwave is driving catastrophic coral loss across the world’s oceans, but new research offers a glimmer of hope for coral reef survival.

As ocean temperatures rise, corals release the symbiotic algae that live in their tissues. As this happens, corals lose their colour and their food source, a process known as ‘coral bleaching’. If temperatures return to normal within a few weeks, corals usually recover. But prolonged high temperatures often cause corals to die from starvation.

In the past, conservation efforts have focused on coral recovery after marine heatwaves. But as heatwaves increase in length and frequency, with shorter recovery periods, conservationists are looking for ways to help coral live through temperature changes.

“The devastating effects of climate change on coral reefs are well known. Finding ways to boost coral survival through marine heatwaves is crucial if coral reefs are to endure the coming decades of climate change,” says University of Victoria (UVic) marine biologist Julia Baum.

But there is good news. A study from UVic biologists offers hope for the long-term survival of coral reefs despite climate change.

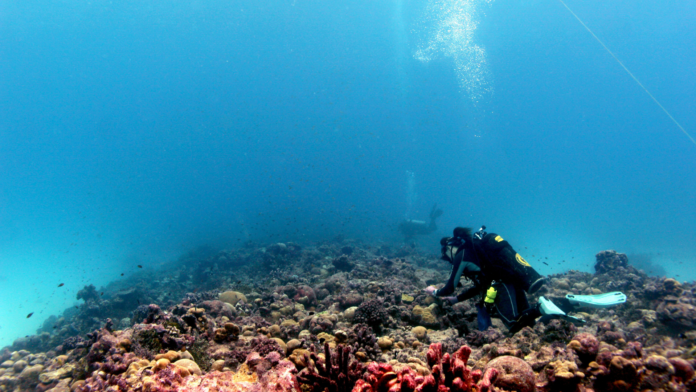

Led by Baum, an international research team studied coral colonies around Christmas Island, Kiritimati. Some near-pristine and largely unvisited by humans, and others disturbed by local villages, wastewater runoff, and subsistence fishing.

Throughout the 2015-2016 El Niño, the team measured ocean temperature, tracked bleaching, and collected coral samples and algal DNA. Unexpectedly, some corals survived the 10-month heat-wave, recovering from bleaching while still at elevated temperatures.

Interestingly, those that survived released their heat-sensitive algae as temperatures rose, and recovered thanks to colonization by heat-tolerant species. However, this only occurred in the absence of human stressors, such as water pollution.

In contrast, corals in highly disturbed areas were already dominated by heat-tolerant algae. Despite initially resisting bleaching, these corals either had no survival advantage or 3.3 times lower survival — depending on the species.

“We’ve found a glimmer of hope that protection from local stressors can help corals,” says Baum.

Danielle Claar, who led the study as a UVic doctoral student, explains. “Although this pathway to survival may not be open to all corals or in all conditions, it demonstrates an innovative strategy for survival that could be leveraged by conservationists to support coral survival.”

The research was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the US National Science Foundation, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Pew Fellows Program in Marine Conservation, the Rufford Foundation, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation and the Shedd Aquarium.